A Writer’s Library – Gábor T. Szántó: „In the first half of your life you collect books and in the second half you realise it’s too much, you don’t want to own all the new books and it’s all right to borrow them”

The Romanian translation of this interview is available here.

I first met Gábor T. Szántó in Târgu Mureș, while attending a literary event at Látó editorial office together with Péter Demény; despite Péter’s attempts to build bridges between two worlds, I was feeling rather lonely in an unfamiliar language and a community mostly enclosed in itself. I was thus surprised by the friendly manner of Gábor, a Hungarian writer invited from Budapest, and his eagerness to learn about the Romanian cultural scene; because of him, I remember that evening fondly. I learned that one of his novels was about to be published in Romania and, indeed, I saw his name in bookshops by the end of last year, on the cover of Gara de Est, cap de linie (Eastern Station, Last Stop).

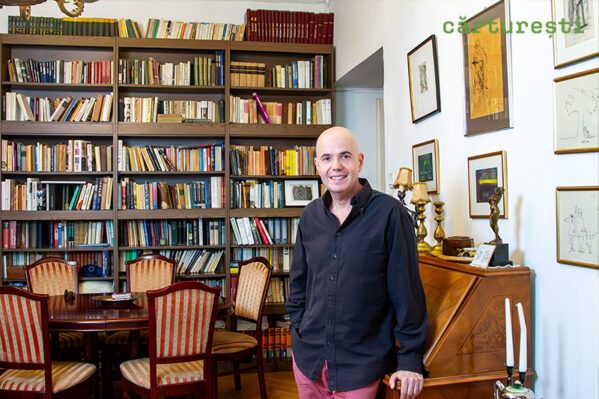

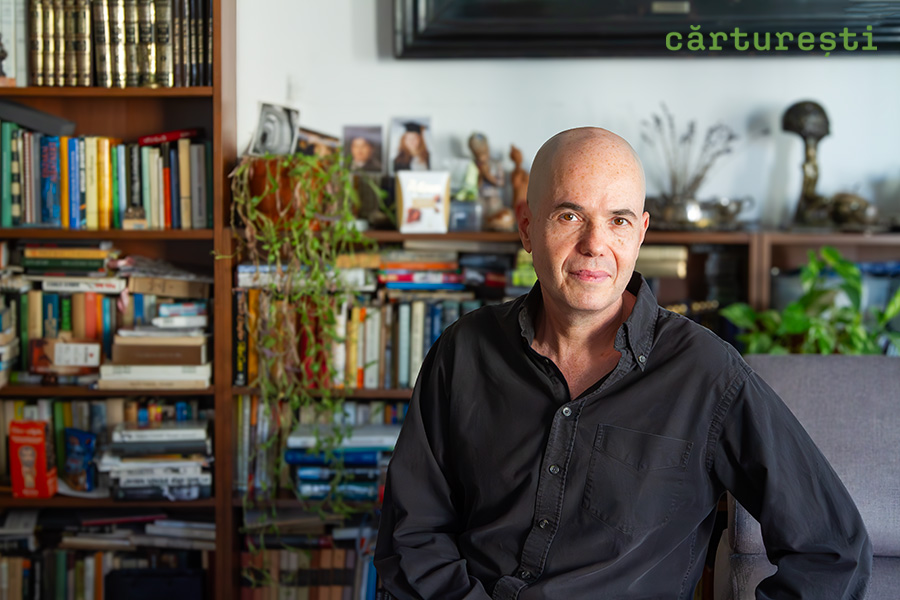

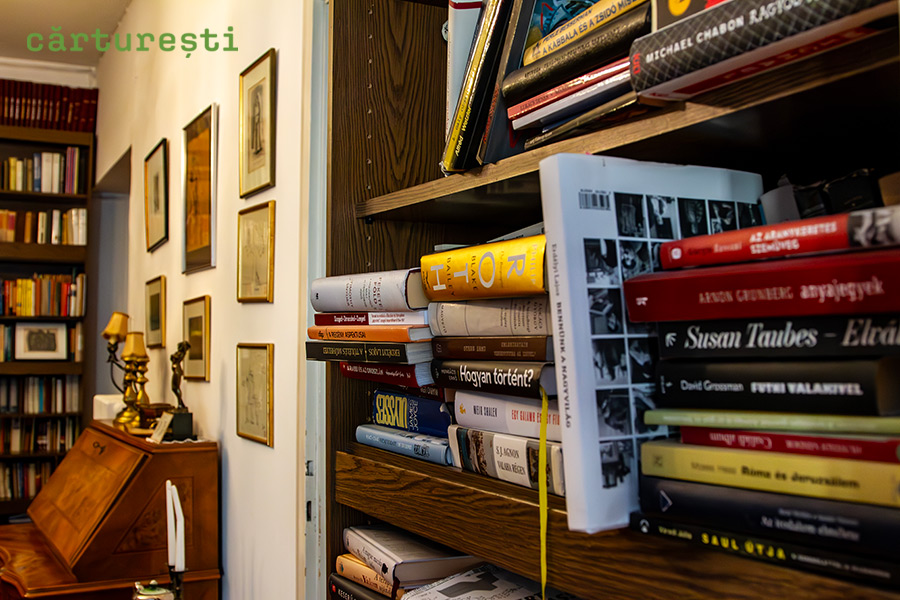

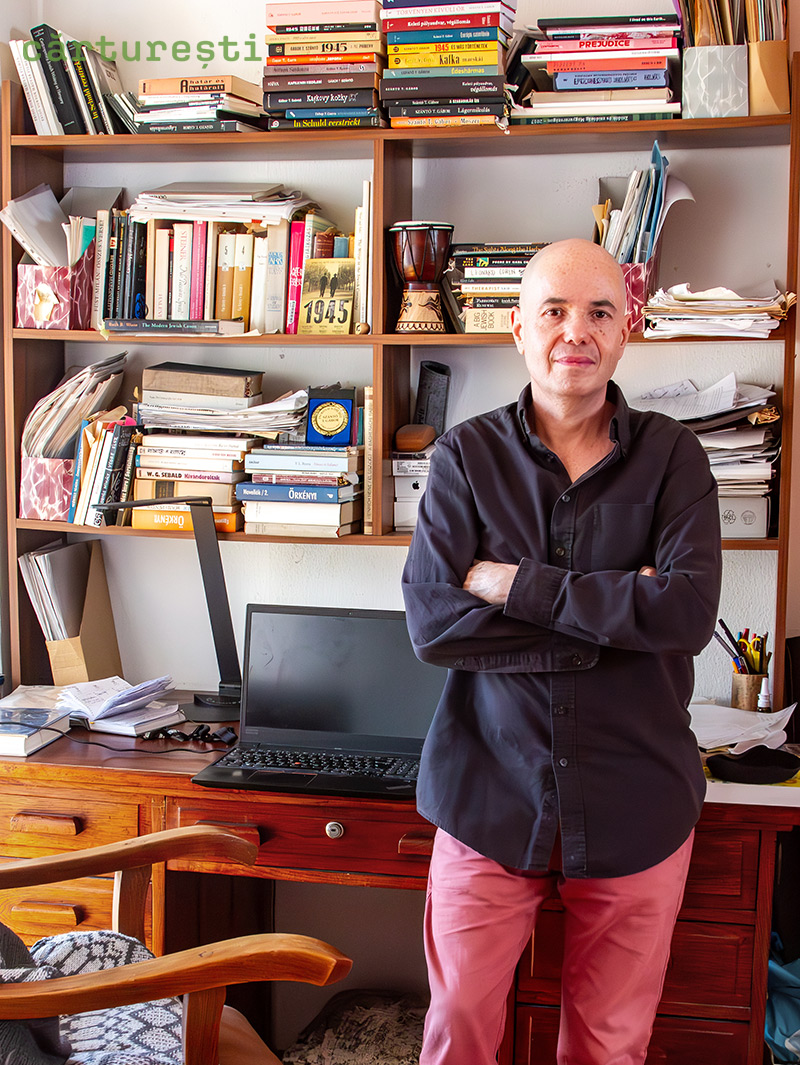

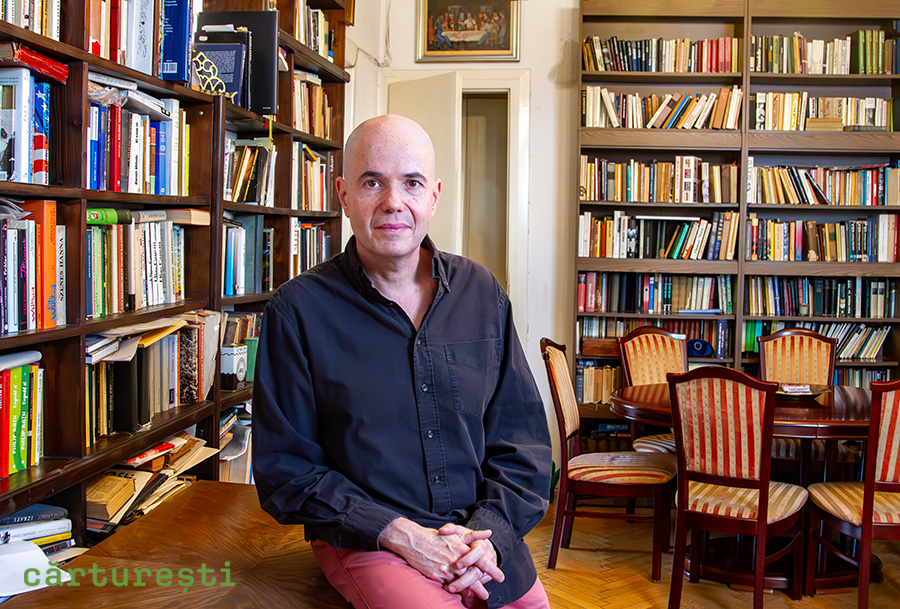

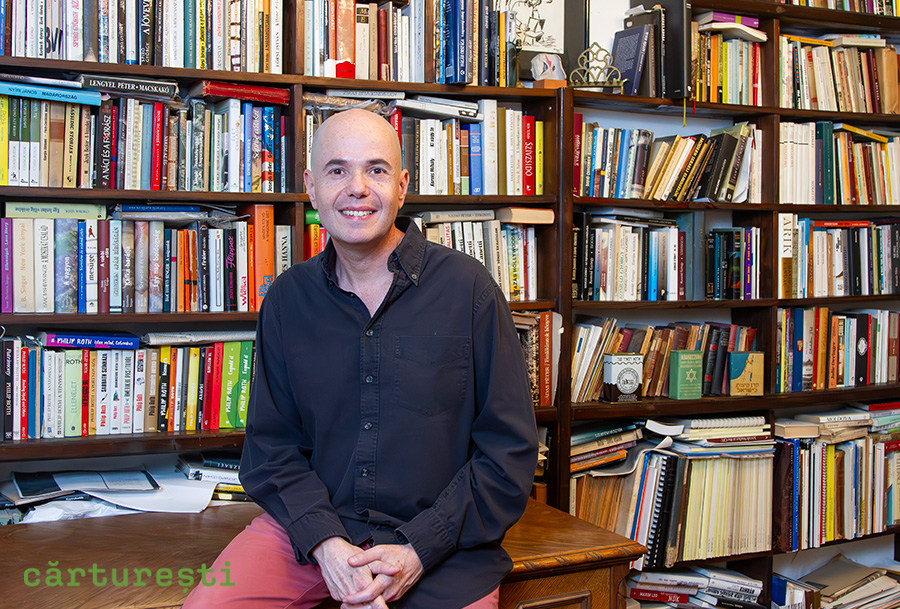

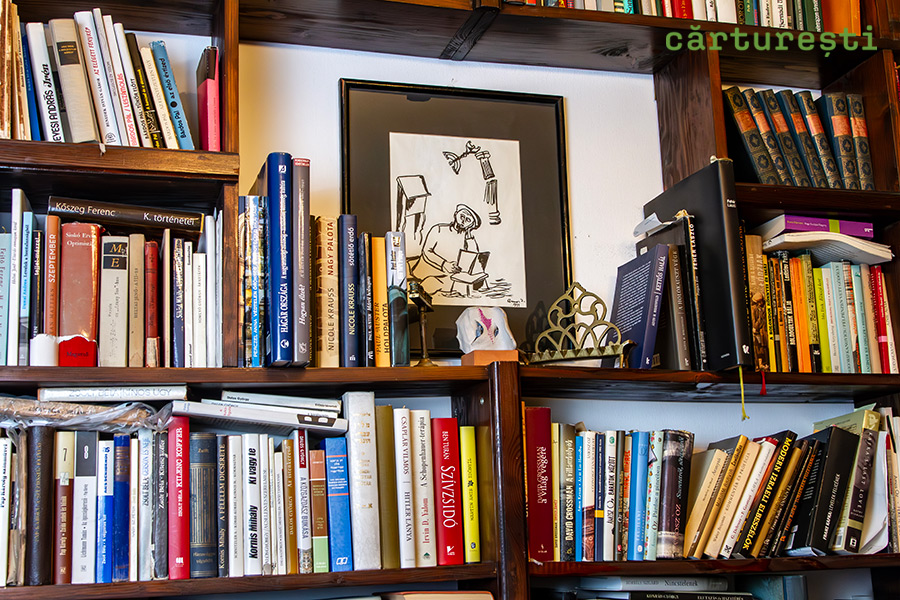

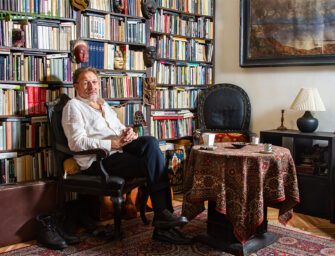

In the meantime, we met a second time in Budapest – and not anywhere, but in his impressive abode from Buda quarter, a beautiful apartment in a Bauhaus-style building, which gave the impression I was entering a memorial house from the beginning of the 20th century. Art objects, antique furniture, a spacious interior with high ceilings, doors with round windows, walls in unusual angles and a huge library, which occupied an entire room and flowed into the adjacent spaces. I wished I had more time to interview Gábor T. Szántó right then for my series about writers’ libraries, but I had to wait for another year, until my next trip to Budapest. I was recounting in the introduction of my interview with András Forgách that I had crossed the streets of Budapest glancing longingly at the beautiful buildings, without being able to visit anything. This time I was lucky and during the three hours prior to my meeting with Gábor T. Szántó, I visited György Ráth Villa, a small Art Nouveau museum with a gorgeous collection of ceramics, tableware and furniture. But let’s get back to Gábor T. Szántó’s library, a reader’s dream come true, where the Hungarian author of Jewish origin has collected thousands of books on his topics of interest – among which the most poignant is Jewish life after the Holocaust, during the communist dictatorship and after the political changes in 1989. On that subject and many others we discuss in the interview that follows.

What is the story of your library, how many layers does it have?

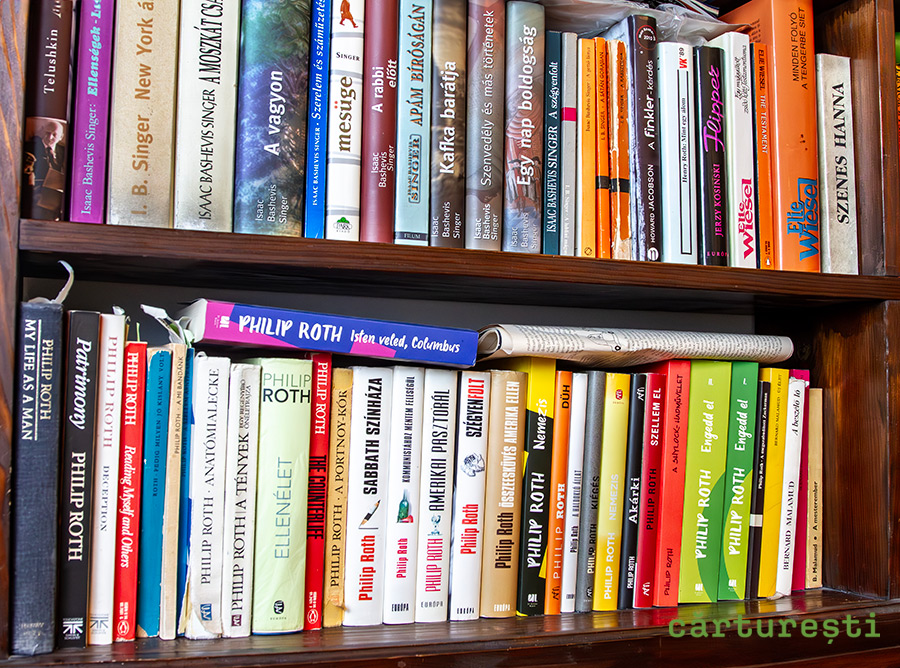

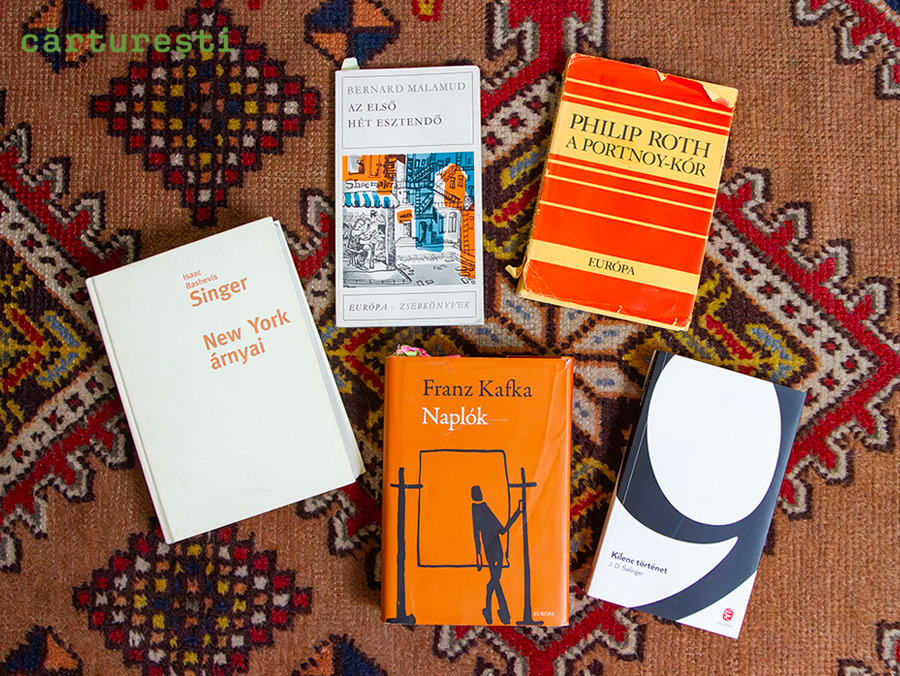

I started to collect books in the last years of my primary school and later, when I was in secondary school. A library closed down somewhere in Budapest and my father brought home a lot of books, mainly contemporary literature, and I started to build a library from this. I also collected some of the books we studied in the secondary school: writers and poets that I liked. Later, in my early twenties, I started to collect Jewish related books, history and prose and poetry. American Jewish writers were very important to me. European writers were also important, but they had written mostly about the Holocaust, while the American Jewish authors, like Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, hadn’t written directly about the Holocaust, their writings were about Jewish lives in general. That was a new tone and it was important for me, because my first strong impression was that everybody wrote about Jews’ persecution and murder, but nobody in Hungarian literature wrote about post-Holocaust life: about what happened with the Jews after. It seemed like the Holocaust was the great vacuum and everything disappeared in it. I realised there was a great gap and I wanted to fill that gap. I wanted to write stories about Jews in a contemporary context, about what happened to the Jews that survived the Holocaust and lived under the times of communist dictatorship. Also, about Jewish life after the political changes, after ‘89.

So contemporary Hungarian literature was important to me, and so were American writers. I also read French and German authors in the late 80s. And classical Hungarian authors – in the 1930s there was an important literary review magazine, the Nyugat. It published Hungarian modernist literature: Endre Ady, Attila József, Miklós Radnóti, Milán Füst.

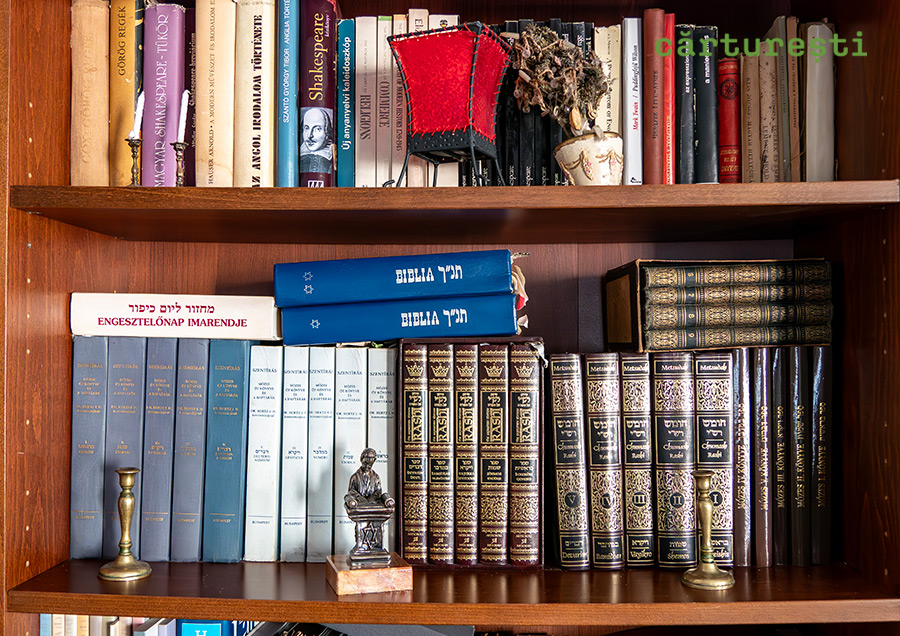

I also have a section in my library with Jewish religious books. I was interested in classical rabbinical literature, but only a few books had been published in Hungary at that time, in the 90s, so I had to find bilingual English-Hebrew books with biblical commentary: Rashi was the most important Middle Ages commentator of the Bible and all of the rabbinical literature. I have eg. the five Books of Moses with the commentaries of Rashi.

Which are the oldest books in your library?

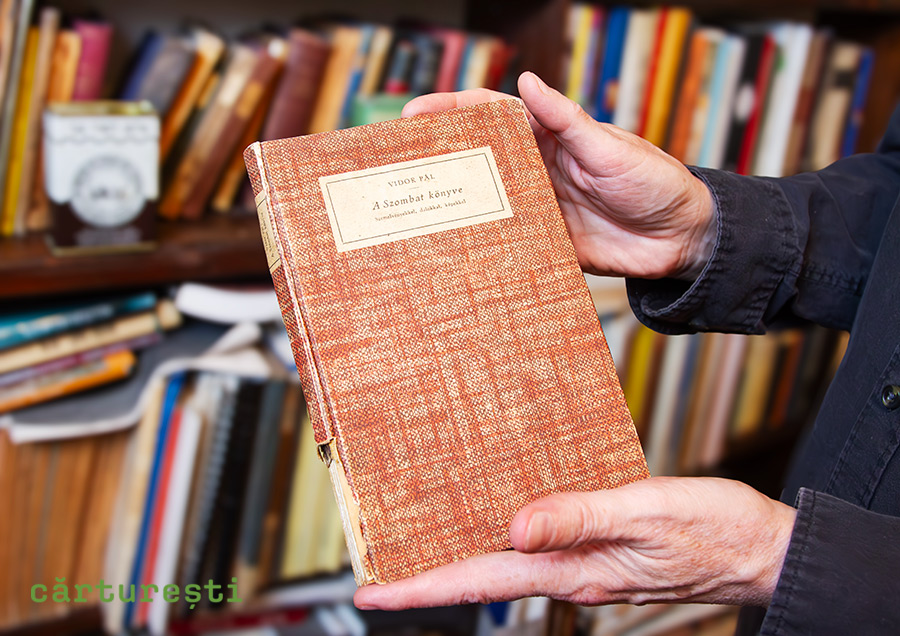

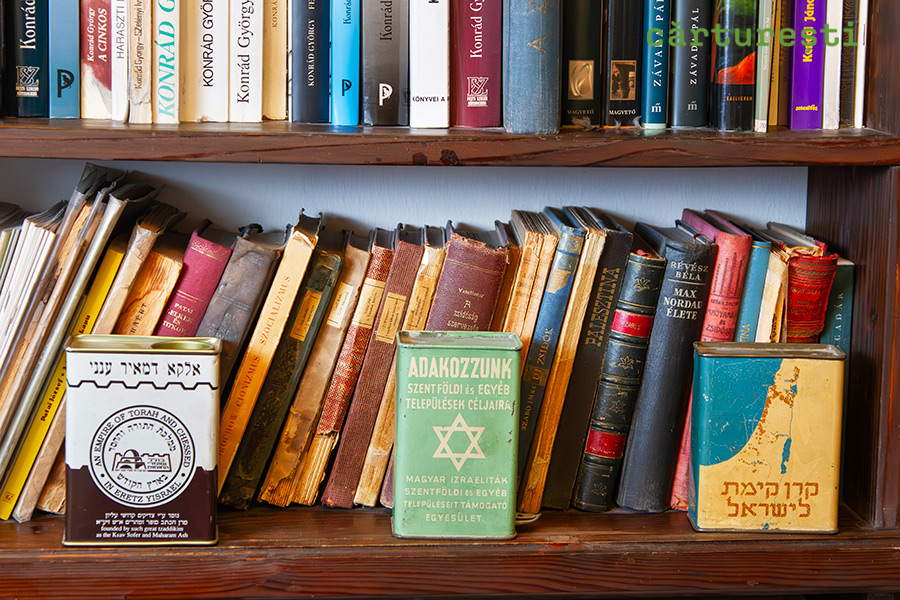

Let me try to figure it out… I have some old prayer books, there are some copies of the Haggadah – the story of how the Jews came out of Egypt, from slavery. Also, there are some Hungarian books from the 1920s: there was a classical series entitled Javne Könyvek (Javne Books in Hungarian ortography). Yavne was a city in ancient Israel where according to the legend, after the Romans destroyed the second Jerusalem temple in 70 c.e., there was a rabbi who asked from the Roman emperor for a city and nothing more: Give us a city where we can teach and live by the rules of our tradition. And this city was Yavne, where the small survivor community started to teach the tradition and, according to the rabbinical stories, this is how Judaism survived in the first century – because the ancient Jewish state was totally destroyed and the Romans took most of the Jews into slavery to Rome. The name of the rabbi was Yohanan ben Zakkai and he asked for a city and nothing more.

The series Javne Könyvek were published in the 1920s and the 1930s after the First World War. There was a small Zionist movement in Hungary, and they published modern Jewish literature: theoreticians like Joseph Trumpeldor or contemporary writers like Shalom Ash. There were around 15-20 books in this series and I have most of them. I liked it because it was secular Jewish culture – a modern type of identity, which was rare in the Jewish life in the 1990s. This type of secular self-reflection is indispensable for modern culture. I used these books when I participated in the creation of this culture, while working as editor-in-chief of Szombat, a modern Jewish cultural magazine. I used the past for creating the future.

Let’s walk around and you can tell me about how you’ve organized your books.

This bookcase was previously for theoretical books, philosophy and psychology, but since more and more books were coming, I had to give up the order and put them wherever I could. So you can see new books in the front line, but behind them, in the second row, you can find the original arrangement… Here is a book with letters of Sándor Ferenczi, a great psychoanalyst.

(We move to the left – e.n.) There’s a story about this section of the library. When I started to grow interest in Jewish literature, I placed the Jewish-related books on these shelves. In the 1930s there was an editor of the Hebrew-Hungarian dictionary, Ezra Grósz, and he has the following definition of Jewish literature: What is Jewish literature? Whatever Jews have written about Jews, whatever Jews have written about non-Jews and whatever non-Jews have written about Jews. It was not a theoretical answer, but it was a funny answer. So I used this definition to create these shelves.

Once, a Hungarian literary scholar came to my apartment and when I told this story to him, he was shocked that I somehow separated Jews from non-Jews: he had a completely different view on this structure and found it discriminatory. (I spot Norman Manea on a high shelf – e.n.) Yes, I have Norman Manea. Here is the series that I told you about, Javne Könyvek, from the 20s-30s. Here are the classical books, foreign literature, German, French, Czech, but unfortunately the cleaning ladies, twice when I wasn’t at home, took the books from the shelves and mixed them up, so in the present moment there is no structure in the library.

(I say I had one question about a funny story related to the library and this could be it – e.n.) It’s a tragicomic story, the cleaning lady. It’s an entire week’s program if I were to put this library in order – we have around three thousand books, so it’s huge work. We’ll organize it when we retire. (He chuckles – e.n.)

(I ask him about the metal boxes displayed on a shelf – e.n.) These boxes are also from the 1920s and ‘30s. This one is from the Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael, a foundation that bought land in Israel. They bought the land acre by acre to have Jewish ownership and they collected money from all over the world. You could find these types of boxes everywhere: in synagogues and institutions. This one is Hungarian, from the 30s – Give to the Holy Land and other Jewish cities. This one is a modern remake of religious study houses. They collect money for the purpose of studying the Torah.

Here you can find the Israeli literature, Amos Oz, David Grossman. (I ask about Hungarian Jewish authors that he likes – e.n.) Imre Kertész, Péter Nádas, some books of George Konrád. And here are the American Jewish authors, Philip Roth, an entire shelf, Bernard Malamud, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and others who published between the two World Wars. (I ask if he has books by Mihail Sebastian – e.n.) There were two of his books translated into Hungarian, For Two Thousand Years and another one, but I read them at the library. Norman Manea also has two or three books translated into Hungarian. This is a Philip Roth biography, an important book. Here are some English books on psychology about second generation Holocaust survivors. Books in English are mixed with the others, I don’t keep them separated.

(We go into the bedroom – e.n.) The poetry is here. Twenty-thirty years ago, when I was writing poetry, I read more poetry books than I do nowadays. I translated American Jewish poetry into Hungarian and also from Hebrew and Yiddish, using rough translations and via English as an intermediary language.

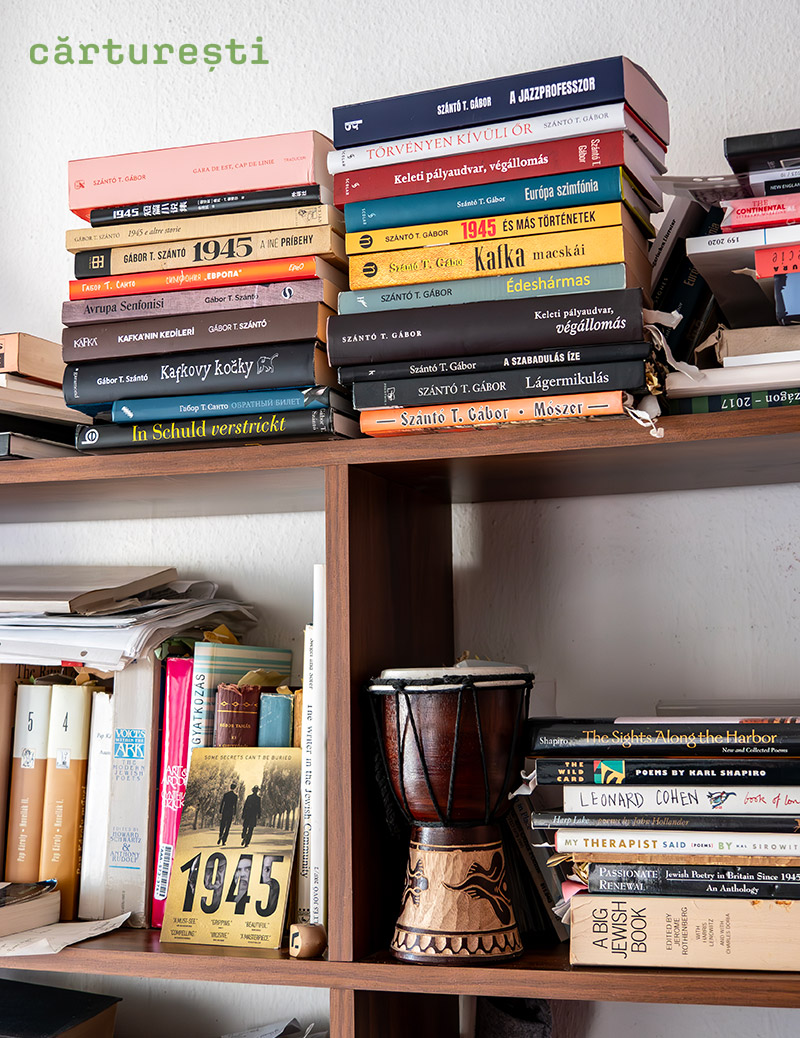

And these are the books I used when I taught Modern Jewish Literature and those up there are my own writings. (He shows me the shelves over his study and grabs a postcard – e.n.) This is the American poster of the film 1945 based on my short story, Homecoming, 1945 – it became an international success and was distributed in forty countries. I participated as the screen writer. It got twenty international prizes. My book, 1945 and Other Stories has been translated into five languages and it has just been published by CEEOL Press in English. (I ask if there will be a Romanian translation as well – e.n.) As far as I know, George Volceanov works on the translation, and hopefully next year it will come out in Romania, too. This will be my second book in Romanian translation after my novel, Gara de est, cap de linie (Eastern Station, Last Stop) that has been published by Editura Cartea Romaneasca in the translation of Francisko Kocsis. The novel that has been published is about three families of Jewish origin with different social backgrounds in 1949, at the beginning of the Communist dictatorship in Hungary. The novel presents how the system destroyed people lives, including those who participated in it.

Do you remember how your passion for reading started? Were you influenced by parents or teachers or someone in particular?

My parents read me stories, and as I was a lonely child, later it was a natural turn to books. When I was 13-14 years old, I was very much interested in crime stories, detective stories, and I read quite a lot of those. Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie, Ross Macdonald, Ed McBain – mostly classical American detective stories. At that time I read almost one hundred such books. Earlier, when I was 10-12 years old, there was a famous Hungarian series about sailors. András Dékány was the author, he was a former sailor who wrote eight or ten such books in the 50s, 60s. Adventures on the sea, on ships, very romantic for a young boy. There was another book, English children literature, with the title Swallows and Amazons, also related to the sea. Arthur Ransome was the author. The sea, water was very important for me in my whole life. In my youth, I took up swimming as a sport and I spent my summer in a village near the Danube with an old couple, friends of the family, and I was always near the water.

You didn’t pursue a career related to water, though…

No, but in one of the novel I have written – it’s not finished yet, I still polish it –, my main character becomes a sailor. Somehow I can connect this back to my life, but there is a deep desire in the main character, a suppressed longing: he goes to Israel and cannot find a job for a long time, and one day he sees an advertisement that a sailor is needed for a fishing boat. And he applies for the job. This will be the third volume of my Kafka-trilogy. The first volume (Kafka’s Cats) has been published after original edition in Turkey and the Czech Republic, and will be published next year in Italy and hopefully in Poland. The second volume, Kafka’s Grave, will be published in Hungary next year.

Can you tell me about the later stages in your life as a reader? I assume the love for reading was constant in your life.

Indeed. After the detective stories, I started to read more serious books. Quite early I realized I was interested in Jewish and Holocaust related literature, which was something not publicly discussed in the 80s.

Do I remember correctly that you also have Jewish roots?

Yes, my family is Jewish. It wasn’t a topic in my childhood openly talked about in society. So, I used the books to educate myself and get more information. My parents talked about their Holocaust stories – they were deported as kids with their mothers, to Austrian work camps. Both my grandfathers were killed as members of the forced labour battalions in the World War II, on the Eastern front in Russia, and my grandmothers were deported from Szeged with my mother and father and other older relatives, to Austrian camps, not to Auschwitz. And that was how they survived. They were deported on the same train. So I became interested in these books and the first one that I read on this matter was André Schwarz-Bart, Igazak ivadéka – The Last of the Just is the English title. It was an internationally acclaimed book, parallel stories that deal with persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages and modern persecution.

What about your favorite genres?

When I started to write, I started with poetry – as most of the young writers do – and at that time I read a lot of poetry to get the sense, to understand the structure of the modern verse and how to write poetry. But in parallel, I read prose, naturally. Unfortunately, I hadn’t read enough history, but only when I focused on special topics for my novels. I had an old master when I was a young adult who told me: A writer shouldn’t read other writers. A writer should read history, because you have your own imagination and you can create your own stories, but you need to have historical basics for your stories. Of course it was an exaggeration, but the main concept was true, and I use history in most of my novels. For example, in the novel that was translated into Romanian, Gara de Est cap de linie (Eastern Station, Last Stop), is also deeply rooted in history.

The Romanian authors who teach creative writing tell the students that reading world literature is key to becoming a good writer.

I know! I read a lot as well. I like to read fiction better than history. But I also consider what my master said that you need to read history, too.

Are there any genres you don’t read at all?

Science fiction. When I was 16-17 years old, I read a couple of classic science fiction books, Stanisław Lem and others, but that was all. I became more attracted to realist literature, mostly contemporary books. Also, historical literature that takes place after World War II and up to nowadays, a context that is close to us and has an impact on contemporary life. The communist dictatorship is the main context of my books. One of them, Europa Symphony, deals with the communist dictatorship in Romania, and half of the book takes place in West Berlin – it contains interconnected stories about two generations. So my characters’ background is rooted in the Cold War and the period of communist dictatorship, as we and our families have a past in that period and our lives were overshadowed by the dictatorship.

Tell me about some books that are important for you from one reason or another.

There are quite a few. For example, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short stories and novels like The Family Moskat or Shadows on the Hudson. Or the stories of Bernard Malamud. These three authors had an early influence on me. From Hungarian authors, of course Péter Nádas had a great impact, also Imre Kertész, Kaddish for an Unborn Child and Fatelessness. I later realized that Salinger’ short stories had an indirect influence on how a childhood can be told.. After you have written a story, you can identify some of the sources that influenced you subconsciously.

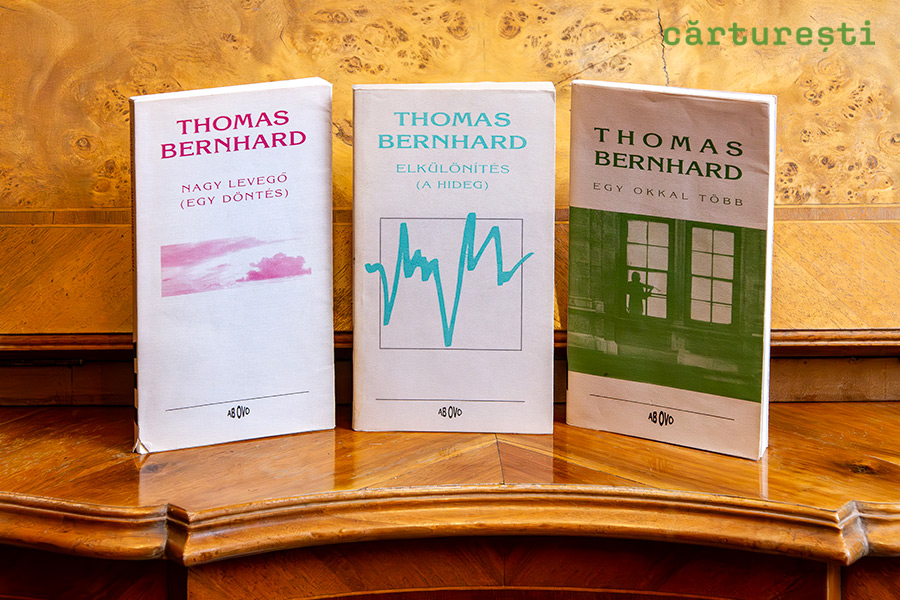

Saul Bellow’s Herzog also had an impact – in my latest book, The Jazz Professor, there is an older man who thinks back about his life wrestling with his memories partly in free associations, partly in chronological order, and although it is based on true facts and I use inner monologue, there are things I can trace back to Bellow. And Eastern Station, Last Stop is some kind of a Singerian book – it contains three parallel storylines that interconnect. In my later years, Thomas Bernhard was an influence. The radicalism, the waves of the language, the monologues, the way he tells the childhood stories… He has a series of five short books on his childhood, I will show them to you. Big Air, Decision, The Cold, The Separation, One More Reason. (The five volumes of memoirs were collected in the English translation as „Gathering Evidence” – e.n.)

Have you made something unusual to obtain a book? Maybe you’ve stolen it?

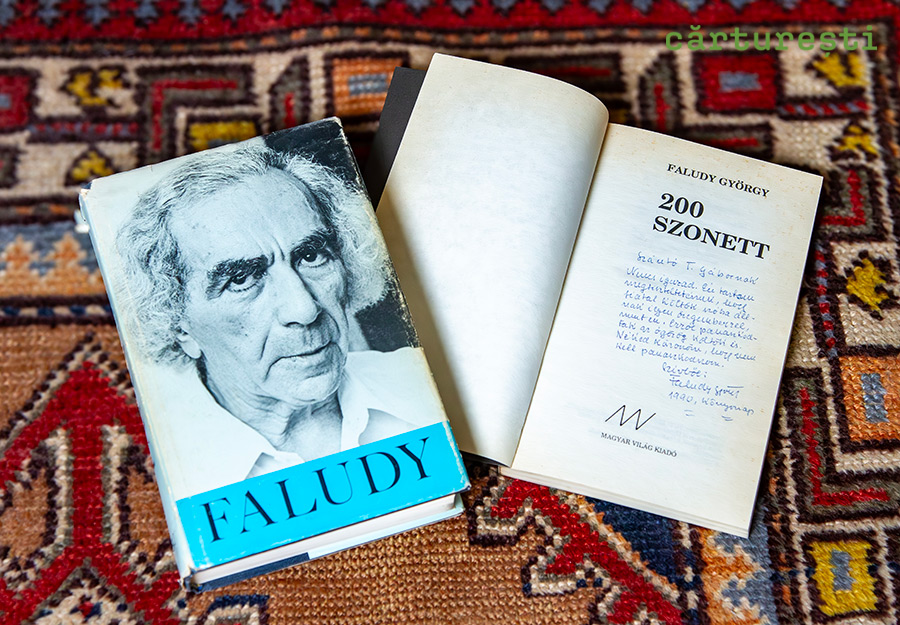

Haha, it happens to all of us at some point that we do not return a book that we desire very much. I can think of a story not necessarily related. There was a very famous Hungarian poet, György Faludy, who emigrated from Hungary after the ‘56 revolution and lived in Toronto. He was in opposition and it was forbidden to publish him in Hungary during the Kádár regime. In ‘87 there was a portrayal film about him, in which he also talked about Recsk, a communist labor camp where he had been sent. I wrote an article in the University newspaper about Faludy, his poetry and the film, and somehow I found his address in Canada, Toronto and sent him the article. He replied, sending me a book of his and we started to exchange letters – at that time he was 70 years old, I was 22 or 23 and we became pen pals. When he came back to Hungary, we visited each other a couple of times.

What a beautiful story! Do you have other similar stories?

There was another poet, Itamar Yaoz-Kest, who emigrated to Israel after being deported to Bergen-Belsen and surviving the war. He started to translate Hungarian poetry into Hebrew and published three anthologies. One of the titles was Magical Deer, the motif of an ancient Hungarian origin myth. He lived in a city called Szarvas, Deer in English, so the title of his anthologies were connected to his birthplace. I started to write letters to him, he translated some of my poems too. We met a couple of times, and once we filmed a documentary with him for the Hungarian television, but unfortunately the footage disappeared somewhere and we never made the film.

Do you have habits related to reading and writing?

A bad habit is that I cannot start reading books till the afternoon, because I feel I must work, I have a drive to work. And indeed, I have my editor job, I edit a magazine, so it’s somehow a moral duty to work. And when I write my books, I feel this necessity too. When I have to do research for some writing I can be a bit more flexible. And in the afternoon, after 5 o’clock I go to the library or I read at home, and I also read late at night. But it’s a bad habit somehow that I cannot read in the morning or during work time. It is especially troubling, when I cannot write for weeks, for months. Sometimes you just have to wait. You should not focus on writing when you cannot write, you need to turn your attention to different activities, to let your subconscious relax, clean, and make space for new ideas. And sometimes I don’t give myself enough space and time, I’m a demanding boss when it comes to me.

(I say that one advice offered by other writers is to stick to your chair and write at least for an hour each day, no matter what – e.n.) I try to write every day, but sometimes it’s not effective. A good advice for writers, though, is to finish your writing day so you have something left for the following day. You should not empty yourself completely.

Can you recommend some less known books that we should read?

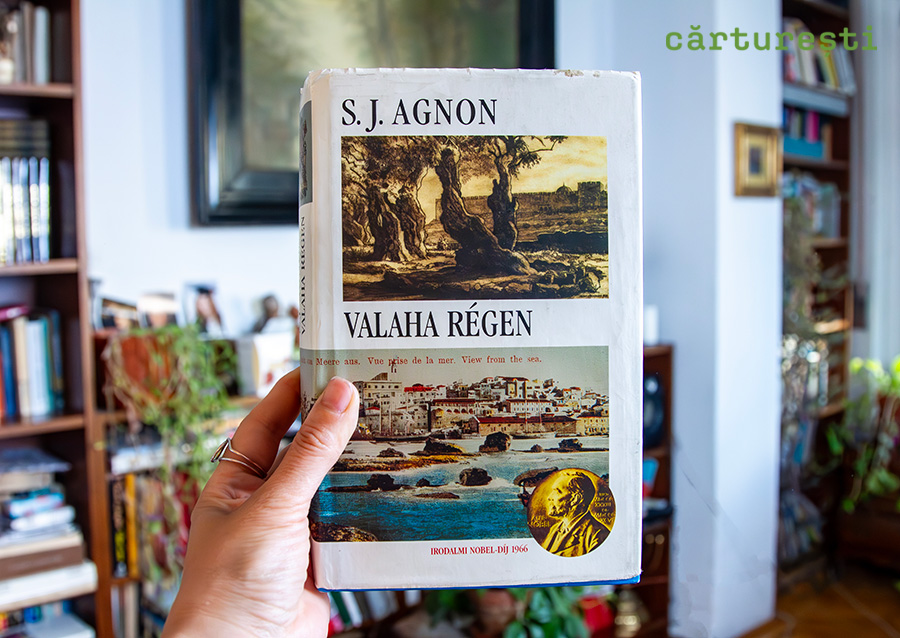

For example, Agnon is a Nobel prize winner and yet he is not well known. He used a language typical for the early ages, the language of the Mishnah, found in classical Jewish literature from the first and second century. So he uses that old, very elevated and formal Hebrew language, but in a modern and personal context, which creates a very interesting mixture and it also works in translations.

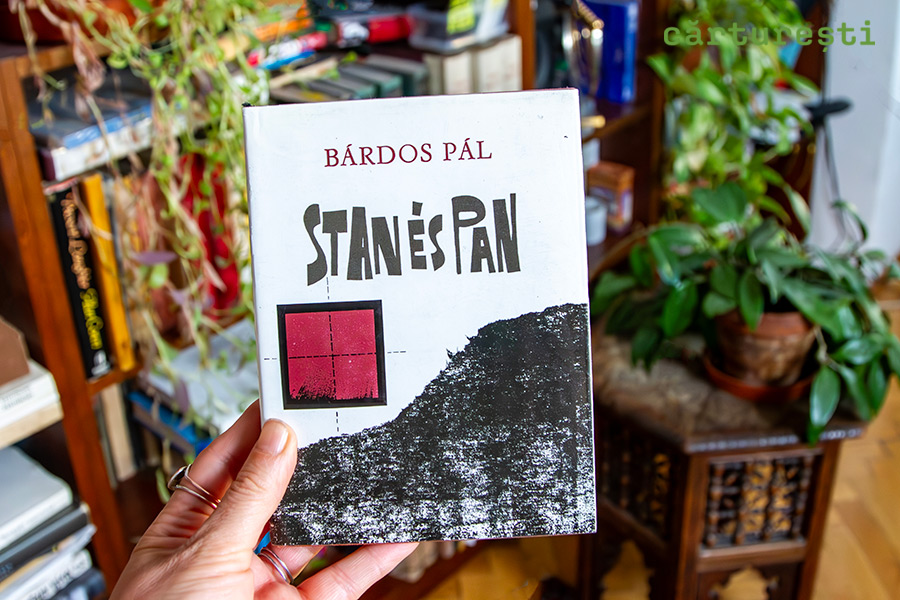

There is a Hungarian author, Pál Bárdos, who has a short novel entitled Stan and Pan, about two Hungarian Holocaust survivors who are somewhere in South America and are trying to catch Mengele. The book is a dialogue, either Stan or Pan is talking, and we begin to realize that they are Mossad agents who are hiding in front of Mengele’s house, waiting for him. Like in the film Laurel and Hardy, they are two absurd figures, tragical and humorous at the same time, and they fight, debating with each other from their hiding places, one intellectual and one less sophisticated guy. It’s a less known book, but a very interesting one.

Also from the Hungarian authors, Antal Szerb, he has a very good book, Utas és holdvilág, Journey By Moonlight. (I say that I’ve read „The Pendragon Legend” and that the modern classics from Hungarian literature are available in English in new translations, unlike Romanian, where the old translations are rather outdated: for example, Magda Szabo’s books – e.n.). Do you also have János Székely translated to Romanian? He has a very good novel, A nyugati hadtest, Western Army. And he has a drama, Caligula helytartója, The Governor of Caligula, in which the Roman emperor wants to put the statue of Cezar into a synagogue and the Jews, who are forbidden to have human figures in their place of worship, try to convince him not to do this. It’s a philosophical drama.

There is a Romanian author, Vasile Dub, with Hungarian Jewish origin, but I’m not sure he has books in Romanian. He wrote short stories which are very similar to the marquesian world. He lives in Marosvásárhely, Târgu Mureș. (I say his name doesn’t sound familiar – e.n.). You should check, maybe he has books in Romanian or he was translated. (I tell him about Andrea Tompa who is more famous, also born in Romania and not yet translated – e.n.) Probably because she has long books which are difficult to translate. But I am sure her books will be translated.

And from Romanian literature, which authors are you familiar with?

I’ve read Norman Manea, Mihail Sebastian with For Two Thousand Years, from the contemporary authors I read the well known Cărtărescu, I also read Ionesco, absurd drama, and I’ve seen a couple of his plays. And of course, Eliade, important religious philosophical books. These were translated into Hungarian. And we’ve seen a lot of Romanian films, because the Romanian new wave directors were very important in the last decade.

Are there any famous authors whom you didn’t like or couldn’t read?

What is difficult for me is the prose of Samuel Beckett. I always think I still have to wait with it. Joyce’s Ulysses is also rather difficult for me. It’s interesting that I used to think the same about jazz, too. My latest book is The Jazz Professor, about a Hungarian musician. Year after year I thought I wanted to listen to jazz and I wasn’t enough of an adult for it. I couldn’t enjoy it. And one day I got this huge correspondence of a family, a few hundred letters exchanged over decades between Budapest and Australia, and I started to write the novel about the jazz professor. The son of this jazz professor gave me the letters, he thought it was a great story of his father and of the three generations, including suffering under the Nazis, the communists, with mental illnesses running in the family…. And for this book I started to listen to jazz for hours and hours, day after day – I worked two years on the novel and during this time I listened to hundreds of jazz pieces. Now I feel old enough for jazz and I started to enjoy it.

Do you keep all the books or you can part with some of them easily?

No, I can give them away. In the last couple of years I did not feel the necessity to buy new books. I can get them from the library. So in the first half of your life you collect books and in the second half of you life you realize it’s too much, you don’t want to own all the new books, so it’s all right to borrow them. There is no place left in the shelves to put the new books on, that is the problem. No wall left for more shelves. (I tell him I can spot some free space on a couple of shelves and he laughs- e.n.) No, enough! I go to the library on a daily basis and I can find the books there. (I am amazed- e.n.) Not daily-daily, but two times a week. During Covid and since then I’ve been working at home, and that is enough time spent in the apartment, so I consciously go out somewhere else to work or to read.

So my question about book buying habits now seems redundant, for example whether you visit the second-hand bookshops often…

In my young adult age I often went to the second-hand bookshops, as I collected books containing dramas. There was a time in my twenties when I wanted to write drama and I was very much attached to modern international books and I collected all that I could buy at that time. (I ask if he has written drama after all – e.n.) I wrote a couple of dramas, yes. One of my plays, entitled Jewish Dog, got the Jackovics prize from Látó Review in Târgu Mureș. I also wrote a couple of screenplays. After writing 1945 I wrote two other screenplays, but nowadays in Hungary it’s difficult to get funding… Also, a producer wants to develop a film from my Europa Symphony, it would be a co-production with Romania, Germany and Hungary, but we still have to wait for funding.

Can you tell me the story of an object from your library?

This is a very funny small decoration Christmas tree. It belonged to Dezső Szomory, a Hungarian Jewish author who got it from Berta Boncza (Csinszka), the wife of the poet Endre Ady. Szomory later gave it as a present to an actress and was inherited through a member of our family, who was also an actor. It eventually landed on me. (I ask how old it is – e.n.) It’s approximately a hundred years old. It’s a funny story with Szomory: his name has an „y”, and when there is an „y” at the end of a Hungarian name, it means it’s an aristocratic family; but he wasn’t part of the aristocracy, he was Jewish. His original name was Weisz Mór and he created his own name through sound play, so Weisz Mór became Szomory.

Ema Cojocaru is a photographer, reader, and literary blogger. She writes book reviews on Lecturile Emei and has published short stories in Revista de povestiri. Every month, she moderates the book club Bibliobibuli.

Any book lover has curiosities about other people’s libraries. That’s how the idea for the column “A Writer’s Library” came about, where contemporary authors are interviewed and photographed alongside their book collections.

There are no comments

Add yours