A Writer’s Library – András Forgách: “My library is a mirror of my family, my obsessions, and the result of an insatiable desire to learn as much as one can in a lifetime”

Găsiți aici varianta în limba română a interviului.

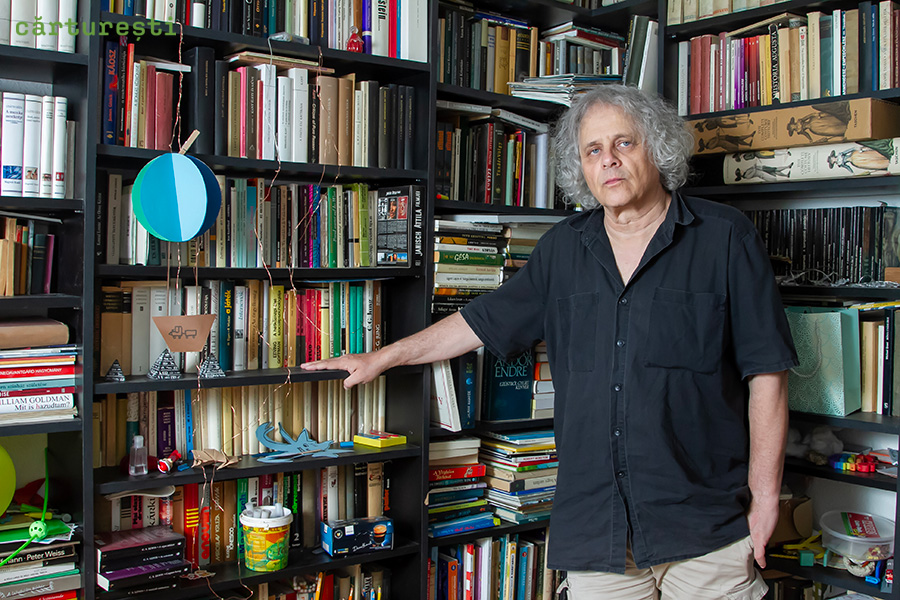

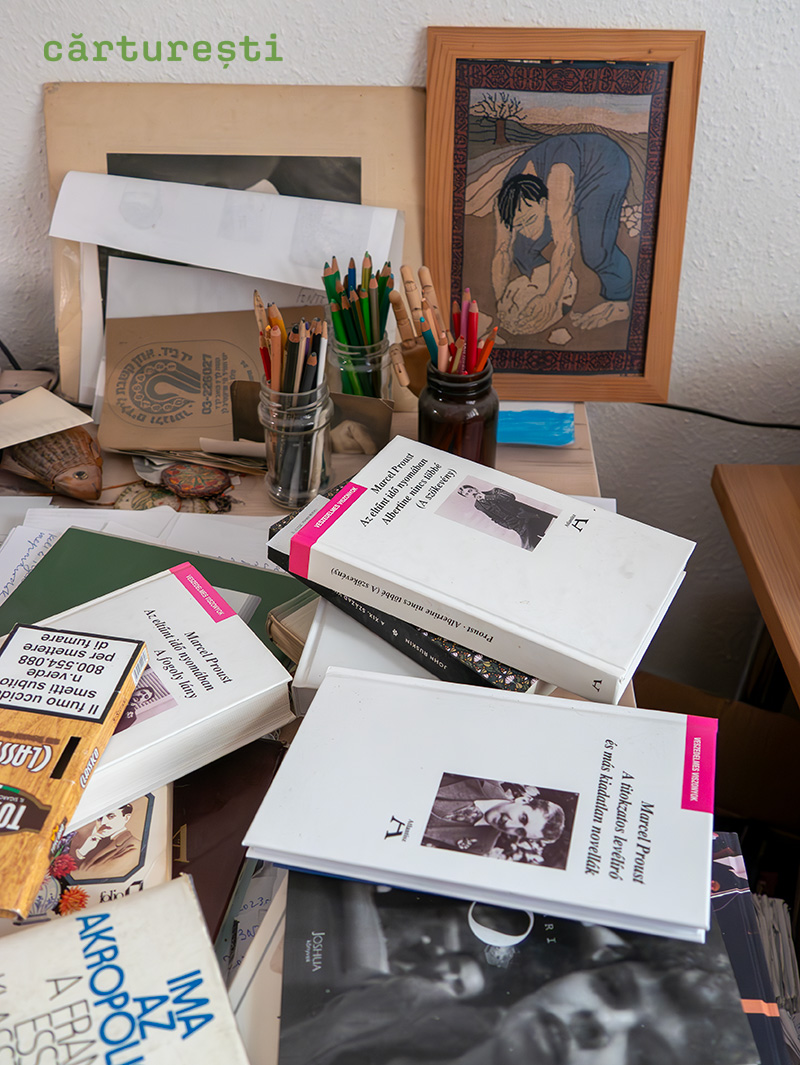

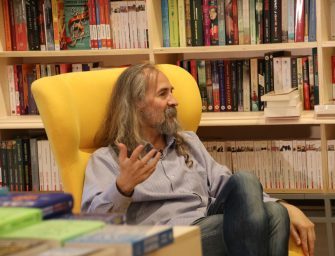

Witty, charismatic, encyclopedic, a great storyteller and a handsome man in his 70s, András Forgách was my first foray abroad for my series about writers’ libraries. I had the chance to meet him in his apartment in Budapest and we spent more than four hours talking and taking pictures, walking back and forth between his study and the ceiling-high library in the other room, passing by Zokni the dog and kind Anna and csintalan Jonatán, who was like Is she never gonna leave our house?, pulling out books from the shelves, some of which I had never heard before, immersing myself in wondrous stories about favorite writers like Joyce or mesmerizing discoveries like Das Echolot, an engrossing talk about world’s literature which had to end at some point because the family needed to eat lunch and the six-year-old son was getting impatient, so me and my partner, Péter Demény, were invited to take a seat at the table, soup & spaghetti bolognese & muffins. It was an intense experience for which I’m grateful, not even minding that my blitz was damaged at the end of the photo session, ’cause sometimes you have to lose something in order to gain something else. Let’s now go back to András Forgách’s study, where our discussion began.

What’s the story of your library? How was your book collection formed?

I should start with a confession: a rather important section of my library doesn’t exist anymore. As a 14-16 year old boy I collected books and brochures of Marx, Engels and Lenin – that was mostly in the late 60s, using up my pocket-money I diligently bought those decaying brochures and pamphlets whose pages were already yellowed and scarcely held together, after meticulous searches on the lowest shelves of the best antiquariats. My parents of course still had the complete works of Stalin which they didn’t want to throw out, even after the big revelation of the Stalin-terror in 1955. I was born into a communist family. And as an adult, after studying philosophy at the university, I had the complete critically edited works of Marx and Engels. Handy, hardcover thick blue books, a lot of them, on the top of my bookshelf.

When I moved into this apartment in 1999, some workers who came over from Transylvania, who could be bought every morning on Moscow square as on a slave-market for a day’s labour, renovated my apartment and as my books piled up, and I had a feeling that I shall never in my life open them again, in a sudden explosion of emotions, I gave them to them, indicating that they could sell them for some money. I remember their faces, they didn’t believe their luck, or thought I must be mad. Those books were very impressive editions and filled many of my boxes. This whole bunch of books was simply too much for me to handle emotionally. Nowadays I’m kind of sorry about it, although I am not sure I would open any of them. Marx especially is a wonderful, sharp eyed thinker and stylist. I still do read him sometimes, in German, on the internet, but those books were for me the symbols of the ancient regime, and I was looking into the future. But this was the seed, the germ, the embryo of my library. It has grown since into an adult and cosmopolitan library, with a very different profile.

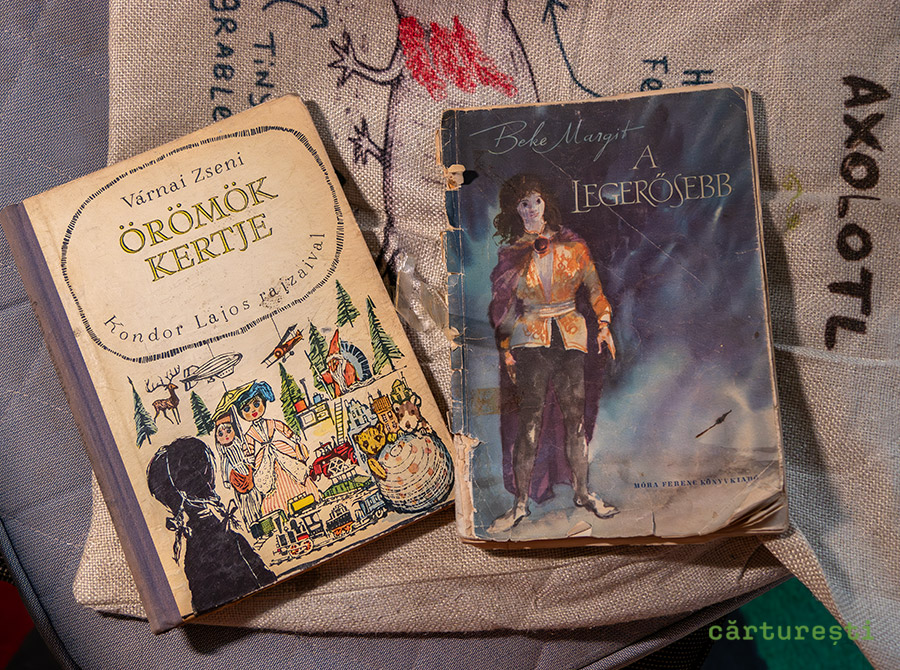

But look, here are two of my really first books, that I read as a child and which I have kept as important, sacred objects – these are children’s books. One is the Örömök kertje, The Garden of Pleasures, by Zseni Várnai. With a beautiful story in it about the child Andersen. And The Strongest, that’s the title, A legerősebb, by Margit Beke – she is still known today as a writer. That was my favorite book sixty-five years ago (it is about the youngest prince who is of course the strongest, that helped me through difficult times in my big and noisy family) and it is still quite close to me. I wanted to read it to my son, but he decides by glancing on a book’s cover, and he didn’t like it. But I regard it as the very first piece of my library.

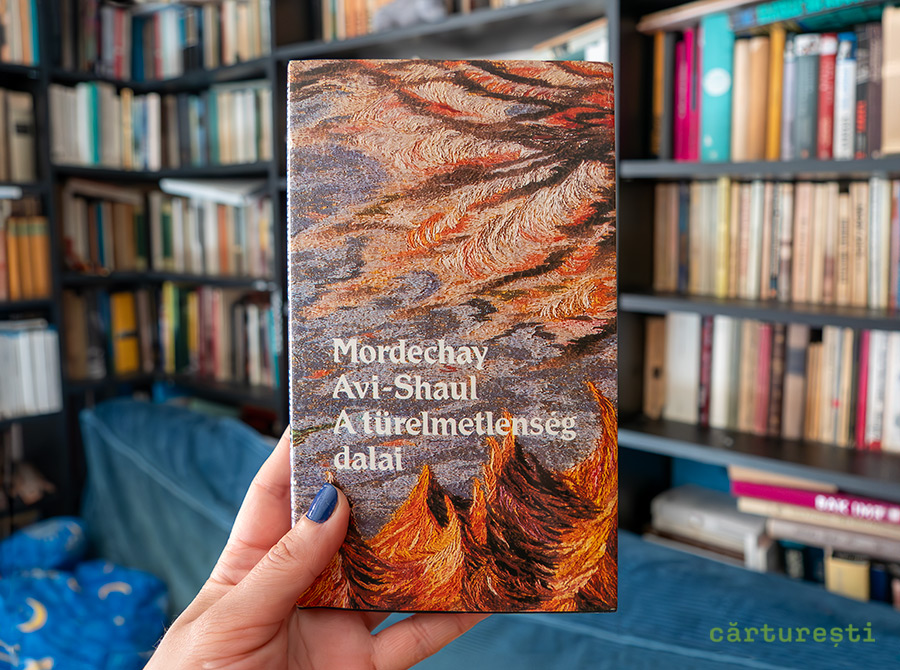

In my family, there was always a big cult of books, of culture in any form. My grandfather, my mother’s father, Mordechai Avi Shaul was a writer, poet and translator who emigrated to Palestine in 1921, and he was a respected translator of high quality, classical German, Hungarian and English literature into modern Hebrew – Thomas Mann, Goethe, Joseph Conrad, Brecht, János Arany, Attila József, Radnóti and many others. Books played always an important role in defining the family-identity. But when I was a child, we scarcely had any books, as my parents were poor. Shakespeare was there, two big books about the human body, big universal lexicons adjusted to socialist ideology (I have them still), some English translations of world literature, as my mother for a long time couldn’t read or speak well Hungarian. I was the most systematic collector of books in the family. I think my mother consciously influenced me to do just that, exhorting the example of my grandfather, who was by the way also a big collector of books.

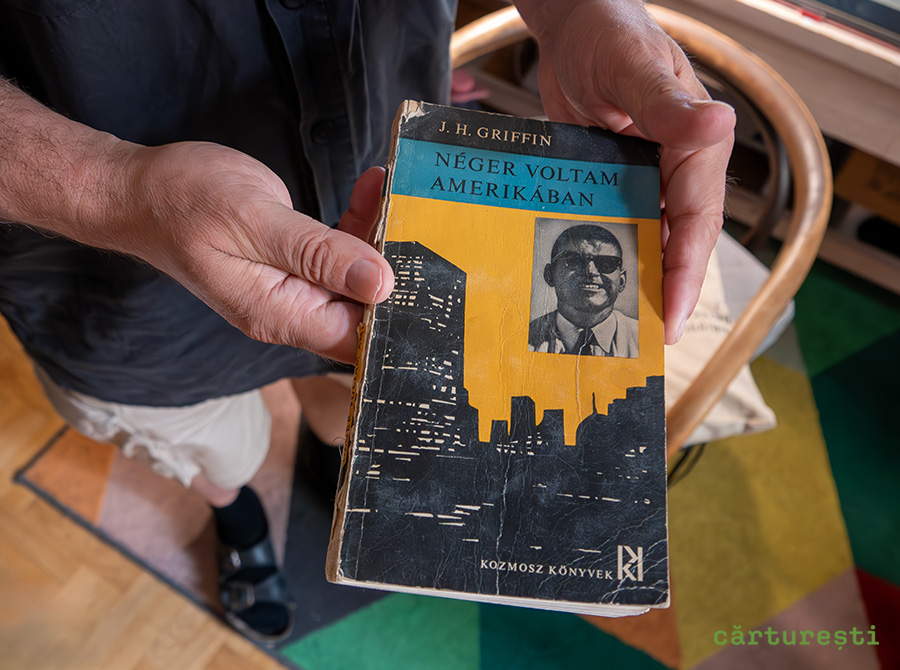

Here are some books written or translated by my grandfather, in Hebrew, and some of his own prose and poetry translated into Hungarian, there are also some books written and translated by my father who was not a real writer, but more of a political journalist, doing hack-work all the time – he translated many books, here is one, it was then a very famous book: I was a Negro in America, that is the Hungarian title. (The original title of John Howard Griffin’s is “Black Like Me” – n.r.) Also my younger sister, Zsuzsa is a writer, so I have her books too, besides my own.

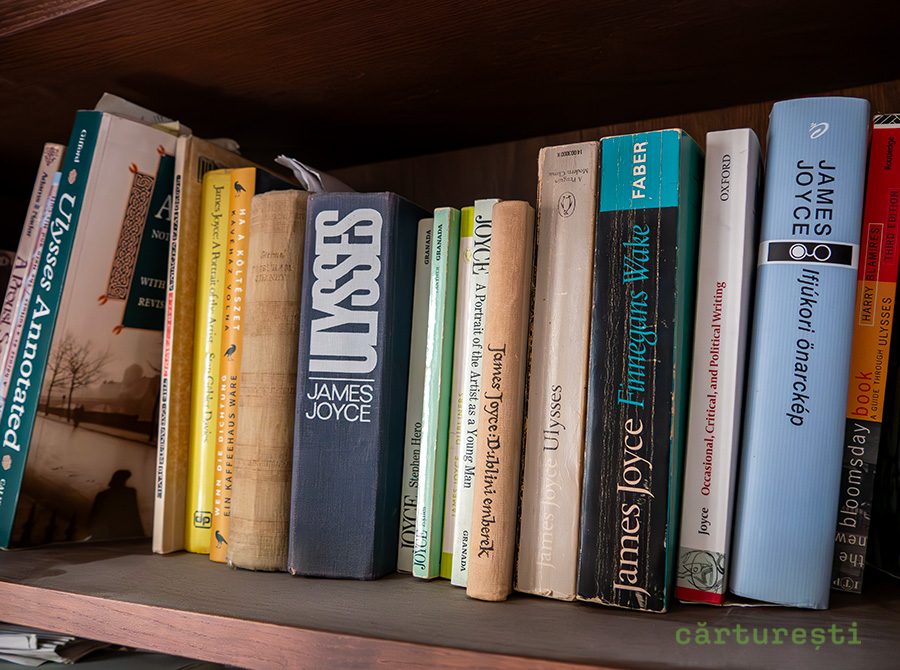

What was very important for me early on, to collect the complete works of my favorite writers. Kafka, Joyce, Proust, later Montaigne, but Joyce was my first big hero, when I was eighteen, besides Dostoyevsky, and I have not only his works but critical commentaries, different editions, translations etc. I am monomaniac – I collect authors I really like, systematically. Hungarians too, of course, the most important Hungarian writers are all here. But there was a general desire in me to have the world literature within hand’s reach. And a lot of philosophy. I was studying philosophy at the university, so Hegel, Kant, Wittgenstein, Schopenhauer, all those Germans, and Plato and Aristotle and Foucault, and Hume and Hobbes, Rousseau and a lot of others. After university I started to work, in 1976 in a countryside theatre, so I have a fat collection of theatre books, plays of famous authors, etc.

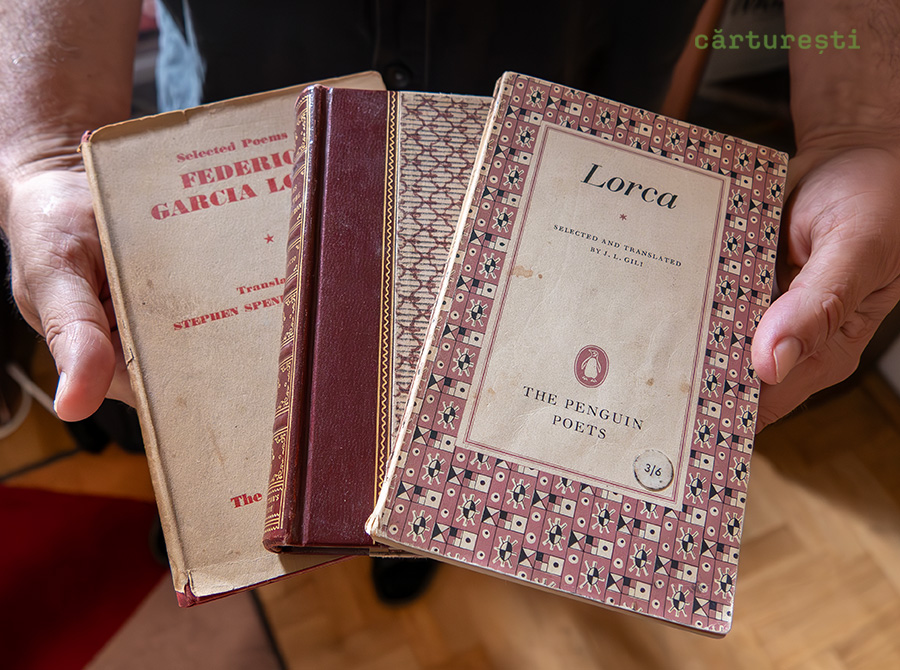

And here are some books of my mother’s early library. She was born in Palestine in 1922 and when she came to Hungary in 1947, with my father – this is a family saga you can find in The Acts of My Mother –, she brought some books with her from her early library, or my grandparents sent them after her. Lorca and Boccaccio in English, because she didn’t speak Hungarian. These are also part of my library now.

My library is a mirror of my family, my obsessions, and the result of an insatiable desire to learn as much as one can in a lifetime. You know what is the case with Jewish families – my family was not religious and it was very important, not only for my parents, but for two-three-four generations before them, the assimilation into European culture, into another nation’s culture, let it be French, German or Hungarian. That also meant an attachment to books, because through mastering a language and literature (or music, or science) you can become part of a nation (at least that’s what Jews thought for a long time, until Auschwitz. It is still true, with some caveats.

My father for example, who was born and went to school in Satu Mare, usually recited poems of Eminescu to me, in Romanian, and very proudly, because he knew a lot by heart, and loved it. He lived in Romania until he was 19, left when the war broke out. I want to show you this picture of my father in Constanța, you see, in front of the Casino, he was boarding a ship to Palestine. 1939, September. That’s his cousin who later died in a Romanian prison after the war. That’s my father when he was 19 years old, with a pipe in his mouth. This is a very important picture for me.

He had a real talent for languages. But my parents were not systematically collecting books. My grandfather had a very nice library. And as a child I was hypnotized by my mother to become like my grandfather – she adored her father and she wanted me to be like him. So maybe that’s one of the reasons I became a writer, who knows. She pushed me very much into that direction.

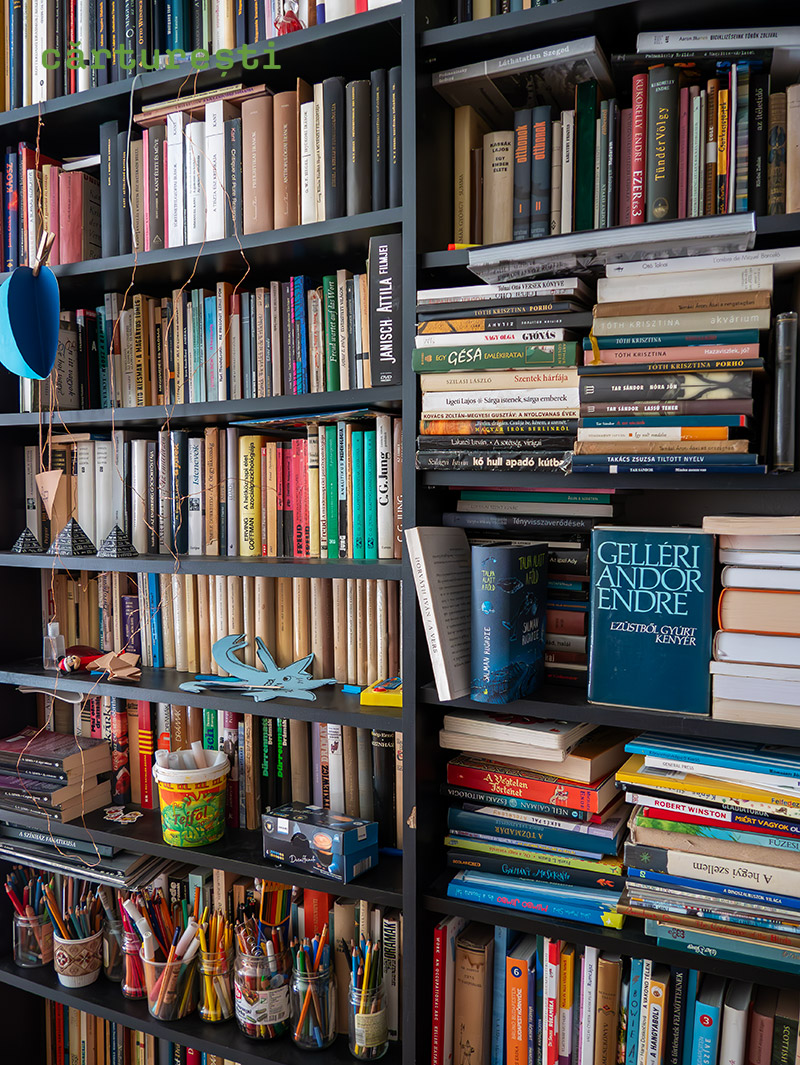

How many books you have now, do you have any idea? And is there a system of arranging them on the shelves?

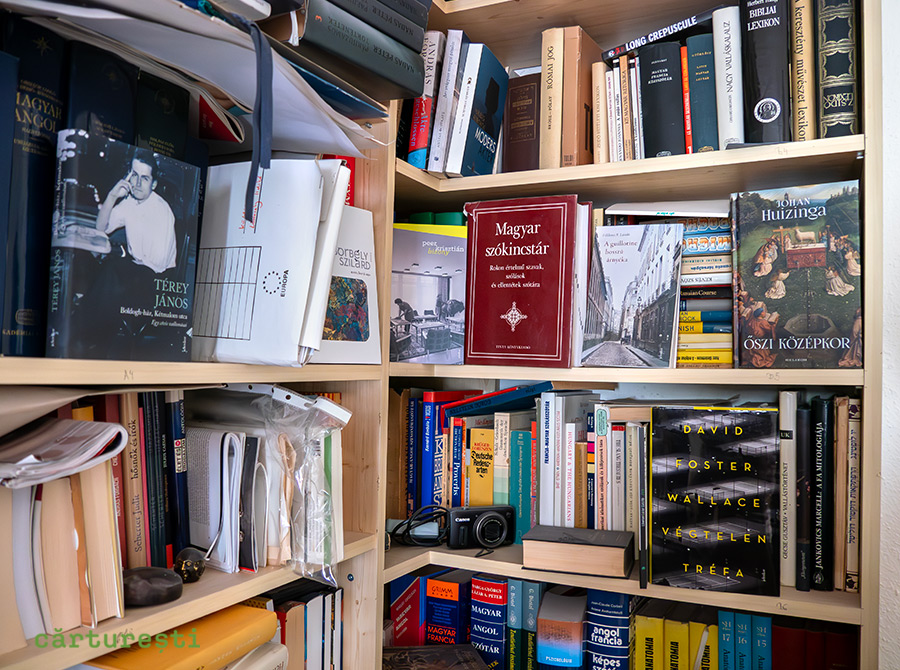

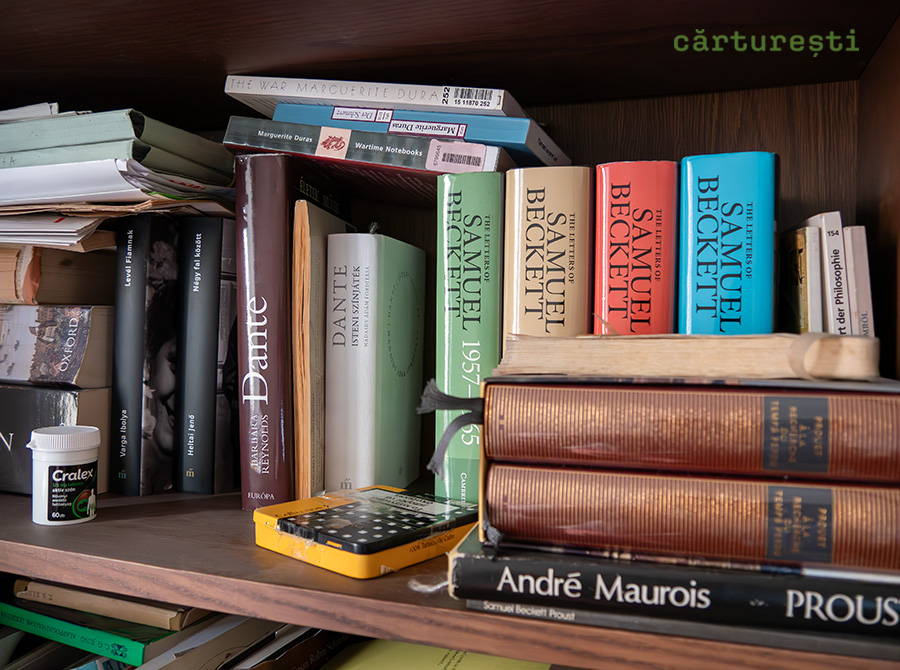

Yes, I have a system and I will tell you about it, but I will also show it to you. The most important books are in this room, my studio, where I work. That’s why Joyce is here and Beckett and Dante and Shakespeare, Cervantes, also a lot of biographies and the books that I am reading actually. (He shows me their covers facing the room – n.r.) Because we just moved in, a lot of books are still in boxes, but here is the throbbing heart of my library.

On this central shelf Kafka, Kleist – I translated a lot of Heinrich von Kleist, Shakespeare, this is all Shakespeare, English, Hungarian, German, whatever, here is Pasolini, here is Pushkin, side by side, Péter Nádas, a great Hungarian writer, and these are my books in a lot of editions, this is the dictionary section, here are all the dictionaries, including exotic languages. Here is Musil, Goethe, Schiller, these classic writers whom I had to have, Flaubert, Pascal. This is the core of my library.

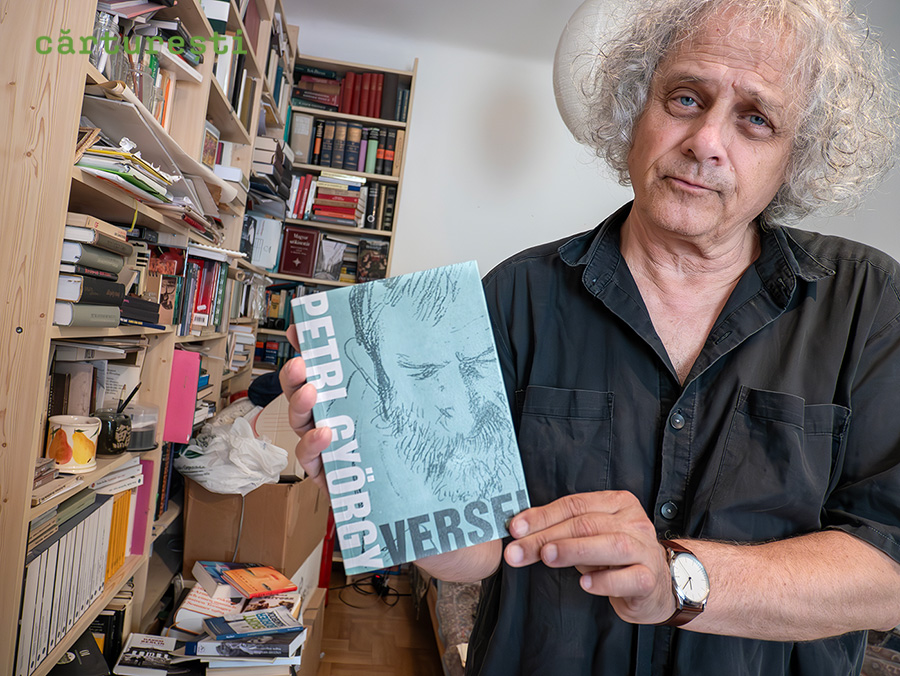

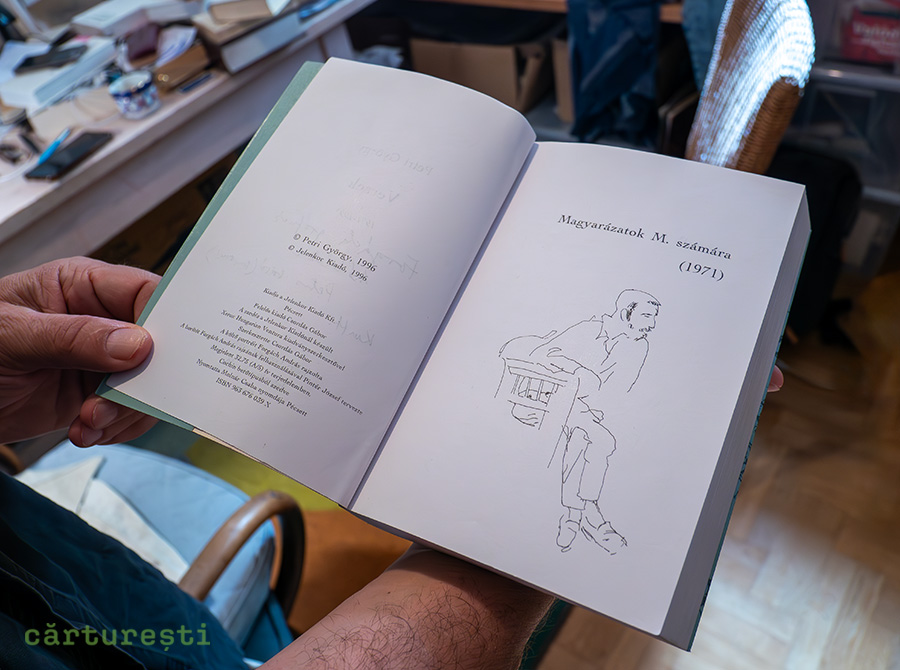

Here a book by my friend, the poet, György Petri – a selection of his poems. Let’s have a look. He has dedicated this one to me and these are my drawings of him. I have all his books in all editions. Also in Samizdat – late 70s, early 80s –, people typed his poetry because he was banned. He died in 2000. He was nine years older than me, but we became very close friends.

It is very important that these books be always within reach. Also some scientific books, philosophy, Sebald, all of Sebald books – I am a great fan, Thomas Mann, but I have many important books in the other room too, so let’s go over there now. I’ll explain you the system there.

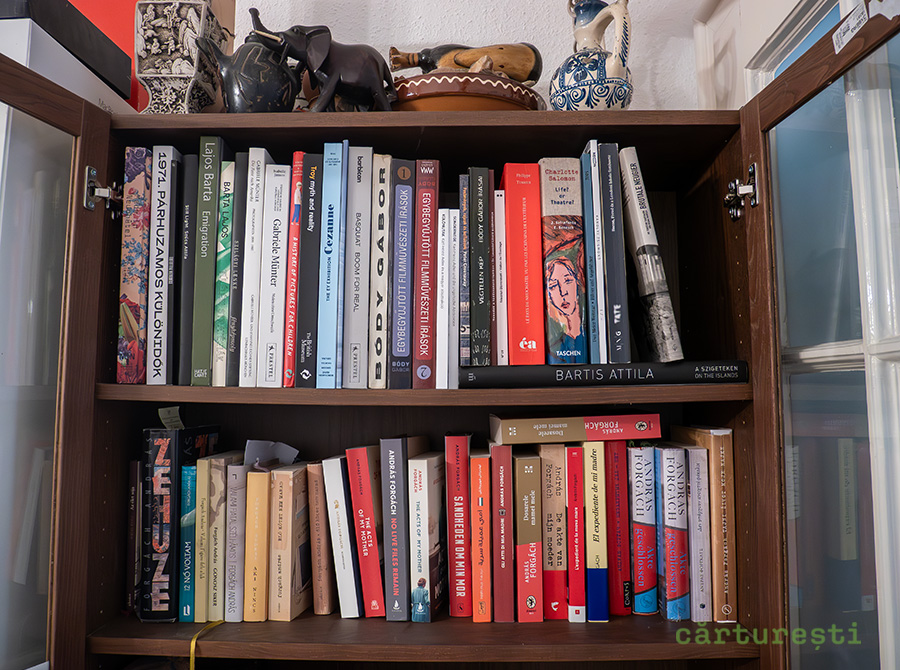

So this is the general collection. Here is the Antiquity, Greek, Latin. This is the Hungarian literature, it flows over there. Very important for me are József Attila, Csáth Géza, Ottlik, Esterházy. Here is philosophy, sociology on all these shelves, here is poetry, here is theatre – plays and books about theatre. Here are huge art books, albums, and also in the hallway and kitchen there is an important art book collection – I also keep my own books there, in all editions.

This is the English section, this is the French – Houellebecq, Camus, Céline –, here are the Russians, these are biographies, these are the Germans – Goethe, Schiller, Canetti –, here Balzac, and side by side with Móricz who is the greatest Hungarian writer, as we used to say. Zsigmond Móricz, all his works. We are still not completely settled here, but the system stands.

My son asks me: Why do you need sooo many books? Those are his books, by the way. His mother arranged his little library on those bottom shelves.

Well, how many could I have? I think four thousand, maybe, or more.

Do you know which are the oldest books in your library?

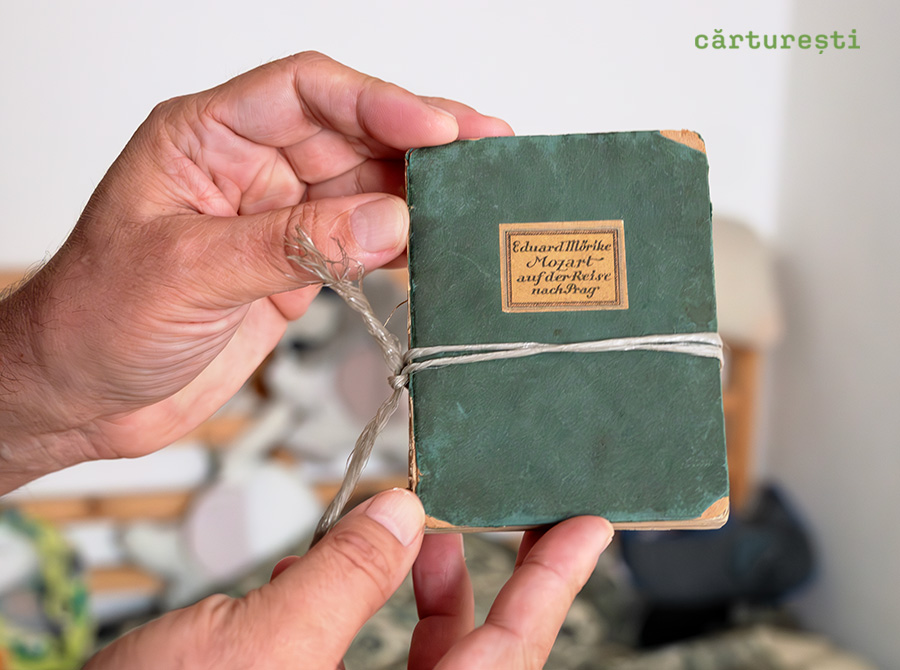

The oldest is not from the Middle Ages, I don’t have such a book. Middle of the 19th century might be my oldest book. I have some from my grandfather, books with Gothic letters. He had a very nice library. He was a poor man, even though he worked all his life, and he bought old books which he repaired – he showed me the winding tiny tunnels those small creatures have bored in those thick old books. He gave me some books, but they are so old that they’re only a relic, I don’t read them, just look at them. I don’t collect very old books.

Do you remember how the love for reading started?

Yes, I do. I was five and I was copying a book without understanding a word of it. It was poetry and I remember very well how I’m tracing the letter “A” although I don’t know which letter is it, and also “M”. It started early, but as I told you, in my family the cult of the book was very important, through my grandfather and also my parents. Even before my grandfather there were many rabbis in the family who were involved with books and it was only natural that we loved them. Compared to my siblings, I was more diligent, more maniac in collecting books. It was a big passion.

I don’t remember from your book how often you met your grandfather?

He came many times to visit us in Budapest, and also his greater family, his brothers and sisters and their children, and he was the king. He was the Big Chief. There are photographies of family reunions where he is sitting in the middle, with his big Einstein-like white hair or earlier with a Chaplinesque moustache under his nose. He was a mythological figure. But I visited him in Israel two or three times and luckily a year before his death I could spend more time with him – I was 34 at the time. We were close friends, he taught me many things.

Here are his books in Hungarian. He was a nice and honest man – and in my early age a very important role model. But he was not a great writer, maybe because some of his rigid ideas or his ideology. His political views were rather sectarian: anti-American, pro-Soviet etc. He was not a Sionist, he was a humanist, in Israel they called him ‘pro-Arab’. It’s not a good position to have in that country, it isolated him almost totally, although he had some admirers even among those who didn’t share his beliefs. He was sympathizing with the cause of Palestine or a two nation state – more than that, he was the president of Human Rights League in Israel and most of the cases were of course Palestinian cases. On the other hand there was the old Jewish tradition which comes from the Torah, the Mishna, the Zohar, it was too traditional, too sublime in its roots. He wrote some very good poems, and a lot of actual political stuff, trying to be poetry, but he was first and foremost a great translator of Thomas Mann. So in Israel they knew him as the Hebrew voice of Thomas Mann. The endless Joseph and his Brothers. He had to invent a new Hebrew for a biblical story written in German. I thought a lot about him when I translated Proust, and I complained and cursed exactly like he did. That’s also part of the heritage.

I have written a book about my grandfather and grandmother, a novel which is partly fiction, partly truth. I will show it to you. Zehuze (pronounced Zeuze) is a Hebrew word which means “that’s it”, “that’s life”, “c’est la vie”. And the letters of the title on the cover are created from the embroideries of my mother. Almost every week for twenty nine years, my grandmother wrote a letter or two to my mother from Israel. When my mother died, I found all these letters. Ten years after she died, I sat down, arranged the letters in chronological order and read them through in two weeks, sat in my apartment, and suddenly a book jumped into my head. These letters were like a big flow, a big river, like the Amazon. My mother’s letters didn’t survive, with some exceptions, so I had only one direction, really like a river. That was the idea. Through my grandmother’s endless monologue we learn the history of my family.

What are the new arrivals in your library which you either bought or received?

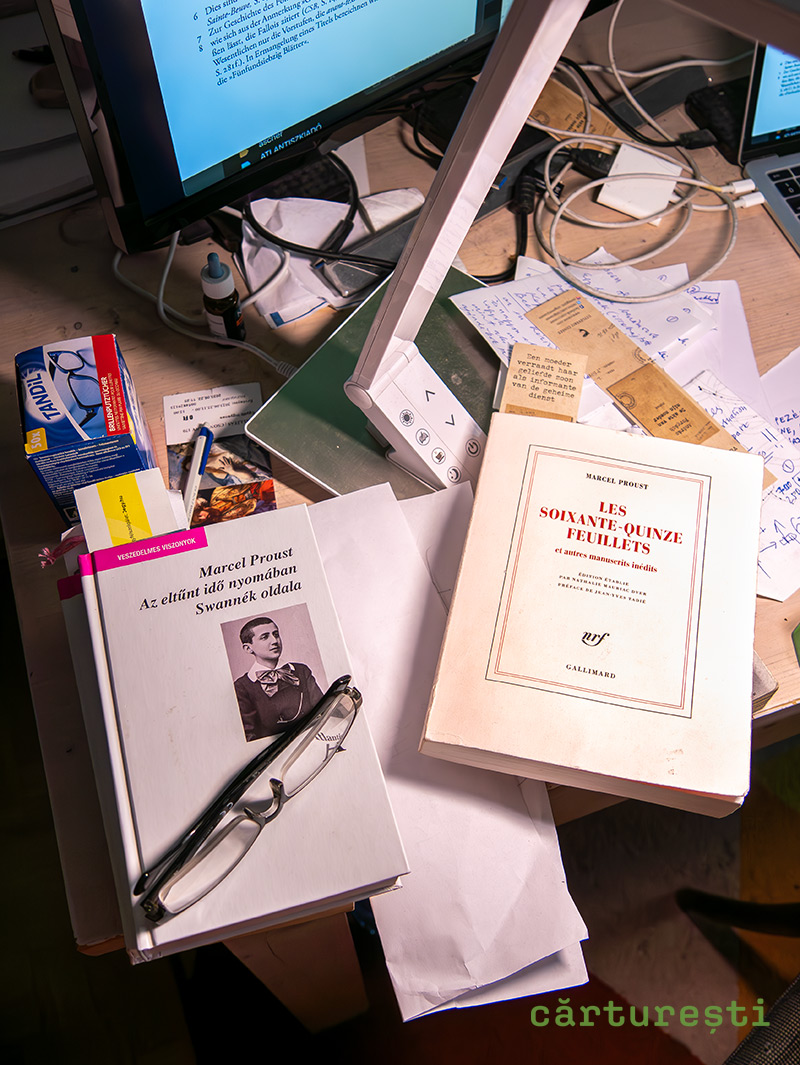

It’s mostly in relationship with my present work, because I’ve been translating Proust over the past year. I bought a lot of books about Proust, editions of his works, biographies, not all in printed book form, some for my Kindle. The book is called Les soixante-quinze feuillets – The Seventy-Five Folios. They contain the essence, the first idea of the big novel In Search of Lost Time. Somebody kept the feuillets for fifty years, nobody knew where they were and they were discovered only after that person’s death. My publisher asked me if I wanted to translate it and I enthusiastically said yes because I wanted to be involved with Proust intimately. What one would call “in-depth reading”. It’s not for the money, because the money is minuscule even for such a difficult text.

I like the books in their physical shape, but I buy a lot of digital books. They are part of my library, but virtually. For a time I almost forgot how to read a properly printed book because of the easy ways of the Internet. So about ten years ago I started to get back to reading real books. My big passion is biographies, I have a quite big collection of them, I showed you a few of them in my study.

Tell me some books that are very dear to you from one reason or another.

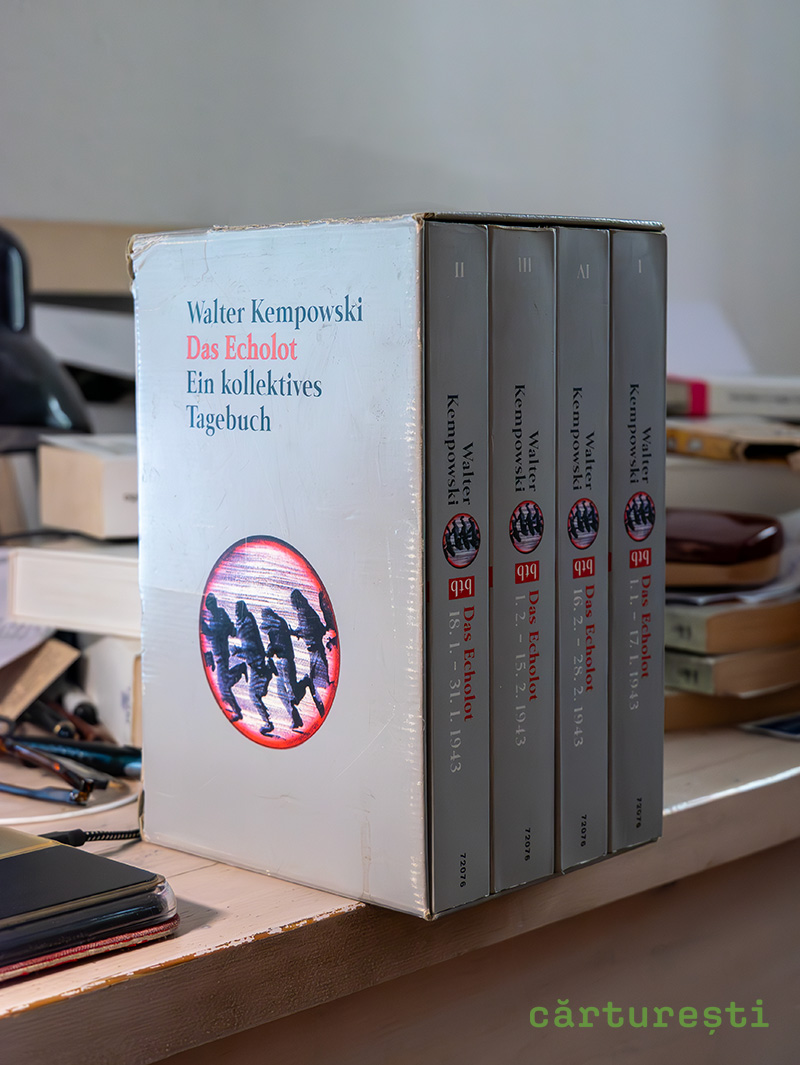

Most are in my study. But I will now show you a book. It is something I discovered by myself, nobody told me about it. (He brings from the study a case containing four hardcovers – n.r.) Here is an author I’m sure you’ve never heard about. If you did, I apologize. Have you heard about Walter Kempowski? (I admit I haven’t – n.r.) This is for me a very important book which I bought twenty years ago. All these four volumes are one book. It’s called Das Echolot. Fuga furiosa. It is a collective diary of the Germans, of humanity. (I remark upon the author’s name that he seems to be Polish – n.r.) No, he was German. After the war he was in the American zone in Germany and when he went to the Soviet zone, as a 16 year-old boy, because his father, who died in the war, was a ship-owner and the Russians appropriated the ship, he was arrested and put into the worst prison that existed in East Germany, the Bautzen. When he was released and went back to West Germany, he started collecting letters of German soldiers from Stalingrad.

Now, the title. The Echolot is the instrument with which a ship can measure how deep the sea is at a certain point, by means of a sound – Echolot. (It turns out the case contains the second part of the work, so he goes back to the study and brings another case – n.r.) So this is the original book, I forgot about it. And this is the second part. The second part plays in 1945, the first in 1943. From January 1st 1943 until February 16th, which is the time of the Stalingrad battle, when the Germans effectively lost the war. I’ll show you the structure of it. When I was in Germany, I read it for two weeks without going out of the room, only taking breaks to eat something and going to the toilet. It’s a fantastic book.

He also wrote novels and he was always hurt that he was not famous enough. Yet he’s a very good writer. Maybe that’s his fate, but at my place he’s famous. It’s not an easy read and it cannot really be translated. All documents, very different, very specific documents. I was thinking about that, how could anyone translate all this linguistically very heterogeneous German stuff. (I find out from Wikipedia that the second part of Das Echolot was translated into English by Shaun Whiteside under the title Swansong 1945: A Collective Diary from Hitler’s Birthday to VE Day – n.r.).

In the Ulysses, Joyce collects all the voices of Dublin, of the Irish people. When Kempowski was once taken out alone for a walk in that very cruel, drastic, brutal prison, he heard a sound like this: Hmmmmmm and he asked the guard: “What is this noise?” The guard replied: “All your friends are talking.” In the cells, people were talking and it came together like this: Hmmmmmm – and Kempowski wanted to create this effect of humanity, so he put together this collective diary. I’ll just show you one day – Friday, January 1st, 1943. First we have Hitler’s diary on this day. Then we have the painter Max Beckmann, what he wrote on that day. Everything is totally real. He collects all kinds of voices, from soldiers, mothers, lovers, the programs in the cinema, the sports events, articles. I read it from beginning till end and I felt like I was swimming in history. Suddenly there’s a letter from a boy in Stalingrad, where he will die, to his mother. And in the next moment an actor is writing to his lover, another man. With this book you are inside the events and there is no commentary, just the documents. It’s one of the greatest things I encountered in my life. Unfortunately you need to know German and be a certain type of reader to appreciate it.

I have another book, everything that people wrote about Goethe. Everything. From his birth until his death. It’s all there. (I comment that this type of book is overwhelming for the “normal” reader – n.r.) I know, but this is what fascinates me. Now that I’m working with Proust, I will go on to collect and read about him even after I finish the translation, because the Proustian universe is fantastic. And to tell the truth, until I started working with this text, from the seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time I read only three and a half. But I was always talking about it very assuredly, as if I knew all about it. It’s also a psychological phenomenon: many books which are here I have not read yet, but because I have a very intense relationship with them, I think that I read them.

If you want to read a book, you have to read it from beginning to end, there’s no other way. (Truly, there’s no other way? I ask – n.r.) No other way. But there is a great Hungarian writer, Ottlik Géza, who said beautifully: You open a book wherever you want, you look at the page without reading the words and the length of a paragraph or two phrases will tell you if it’s your book or not. And then you close it and put it back never to open it again. A critic cannot afford not to read a book, but a writer or a reader, why not? His idea is beautiful because he’s looking at the visuality of the page and the music of an accidental phrase. (I tell him this method sounds paranormal – n.r.) Yeah, good writing is paranormal.

For Proust it was essential, one of his great discoveries, that consciously you will never get to the truth. If you have luck and you always strive towards it in a way, then maybe. Your truths are hidden in objects, that’s what he says. But it’s true that books are also magical objects, otherwise it doesn’t make any sense.

When I was eighteen I went to the University and there I met a guy who told me: read Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Dostoyevsky, Devils. These two books. And then I started collecting Dostoyevsky. Joyce was not very common in Budapest back then, it was 1971 and I couldn’t buy his books, there were no new editions. So I went to the library and read all his works sitting there. I don’t know if you’ve ever read Ulysses, it’s a truly difficult book, it doesn’t give itself, you have to read studies and commentaries before it to be able to understand it. Otherwise its very convenient to say: Come, book, and be good to me! Make me like you. I want to enjoy you. But not every book is like that. Some books you have to stage a real fight to get close to them, to have a mutual understanding. The book will understand you, if you understand the book.

Béla Bartók, the great composer, said that he had to listen to Schoenberg for two years and study him to be able to enjoy it. You know Arnold Schoenberg, you know the atonal music – a great composer, all the modern music begins with him, because he invented a very different tonal system. Bartók was in another tradition and he said: I have to know what this Schoenberg guy is doing! You can’t just listen to it and say: No, it’s not good. Some things you need to work for. And Joyce, I had to work very hard for it, for Ulysses. I have about five commentaries on my bookshelf as companions for just understanding it.

Joyce has a lot of admirers in the world, he has a cult, but many people say: I don’t wanna fight for this, because I can’t enjoy a book for which I need commentary. But it’s not true. Shakespeare – if you want to translate Shakespeare and you want to understand his work in all its depth, you need the science of it, you need to learn the language, it doesn’t work otherwise. Of course, Dostoyevsky you can read without commentary – Crime and Punishment, Brothers Karamazov. But even with Dostoyevsky I was reading his biography and his wife’s letters and memoirs, in order to understand the man behind the novels. Some people, even clever people, say that if you need the biography to understand the book, then you will never understand the book. I don’t agree with that. Other people say that novels and biographies have nothing to do with each other. But I need it, I need to know more about a writer. Every life is so interesting, so special.

Are there writers you don’t like?

Yeah, absolutely. I do have very strong antipathies. For example, a great writer like Flaubert. He was very resistant to me. I fought to be able to read Madame Bovary. (I ask if it was boring or too wordy -n.r.) I wouldn’t say boring. It’s very hard surface. He has a philosophy of impersonality – he takes the person out of the way of telling the stories. He wants to be sooo objective. So there’s this yellow, golden thing that’s hanging from the window sill (He points to the open window behind me – n.r.) My wife put it there so that my son can see it from the street, to see where we live. It’s beautiful. And when the sun shines it throws golden glimmers over the ceiling. Flaubert would write about our scene, the two of us, now, our present conversation, he would start with a very strong description of that shining yellow object at the window, and that’s more important for him in a way than the two people sitting on a sofa, and their psychology.

I don’t know if you remember the beginning of Madame Bovary. It starts with the description of a strange little cap sewn together from very different materials, on the head of Charles Bovary, when he’s entering the classroom and everyone is laughing at him. That’s Flaubert. Its fantastic. It’s his invention, he started with this position, the impersonal, the world as a surface. And at first it made it difficult for me. His music is not quite the music I like, but he’s a great writer who you should read and I’m very glad I did read. I also wrote a play from his last, posthumous book, Bouvard et Pécuchet. It’s a parody of science in the 19th century, about human stupidity, the destructive power of commonplace.

With Joyce, who is also Flaubertian, like Kafka was – they are very different writers, yet the greatest in their eyes was Flaubert –, with Joyce I’m there with the music, not only because my English is better than my French, but I like his way of making phrases – he’s a very great musician. (I tell him that he seems to be a gifted teacher for his students – n.r.) I’m not bad. I just gave a course about Shakespeare’s sonnets for theater directors this past half year and they liked it. You know, my grandfather was also a teacher so my mother wanted me to be a teacher as well, but I had to learn by myself how to do it.

And some other writers you don’t like?

For example, here’s this guy, Céline, I have many books of him. Here you can see all his works in French, also some in Hungarian, Journey to the End of the Night. I can appreciate he’s a great writer, but I don’t like his works – not because of his antisemitic views, but it’s very difficult for me to catch on with him. And here is his biography, I bought it twenty years ago. It’s a very interesting biography, by the way, because it is not chronological. It’s written from two directions all the time, from the end and the beginning. Have a look. It starts with the end. 1961, 4th of July. So I love this biography, although I hate the guy.

And here is a great French writer, Marguerite Yourcenar. Difficult for me. Interestingly now, I speak about French writers, because their books are in front of me. Camus was for a long time difficult to read, but now I am totally involved. (I remark upon the phases in a reader’s life and the changes in taste. I tell him that Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu told me in an interview that he was no longer impressed by magical realism the way he was in his youth – n.r.) Oh, very nice chap, I met him in Bucharest. And he’s a good writer. I read his book translated into Hungarian, an autobiographical thing. And he’s a fantastic publisher.

Apart from Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu, have you read Romanian literature, are there any books you liked?

I read Panait Istrati when I was an adolescent, Chira Chiralina. I loved it. I got to it accidentally. And Gabriela Adameșteanu is an author I’m reading, I have some of her books in French, also. And Cărtărescu is a very good writer. Very high quality writing. And of course the old playwright – not Ionesco, not Matei Vișniec, although I like him very much, no, two centuries ago, the big Romanian writer. (Caragiale? I offer – n.r.) Yes, Caragiale. He’s fantastic.

What about Hungarian literature, what would you recommend from both classic and contemporary books?

From what I’ve gathered, Hungarian literature is very well represented in Romania – you have Krasznahorkai, Nádas, Sándor Márai, Esterházy, Bartis, Dragomán, and in good quality translations. They told me that my book was very well translated by Andrei Dósa and I believe it (We talk about the difficulty of translating a language that has no genders and I tell him about a certain scene in his book that made me wonder about his sexual preferences – n.r.) Yes, there is a person in that book, a young guitar player whom I did have an affection for. You felt it well, absolutely.

That scene was constructed from lots of events put together, from what happened in that apartment where we lived as children and that later became a huge place for the Budapest intelligentsia. We had a theater, a lot of people slept there, I didn’t even know them all, they came and went and this guitar player later became very famous in an Avant-Garde band, but he also became a member of a religious cult and published a book about his life. And there he writes beautifully about my mother. That’s why I mention him in my book. He writes about our friendship as well. The biggest part of his book is about this religious, sectarian stuff, quite boring – he was the member a sect that is very powerful in Hungary even today, but the other part of his memoir that tells about life in Budapest in the 70s is excellent.

Is there any underrated Hungarian writer you’d like to see translated? Into Romanian or other language.

They are discovering them. Antal Szerb, for example. In Germany, in England, in America he’s becoming known. (I ask him what he thinks about Magda Szabo, if she’s too sweet – n.r.) No, no, no, she’s deservedly famous in America, in France. She’s not my type, but I think she’s a very good writer, the readers like her. Also she had a big influence on a generation of young writers. The first book I read was The Door and I was surprised, Emerenc is a fantastic figure. But the lies are there in the words, she couldn’t write the full truth so she had to go around it, I could see it clearly. I’m sure you have some good writers in Romania who had the same problem under dictatorship.

Do you have favorite literary genres? You mention biographies a lot.

Yes, biographies are absolutely at the top. A good biography is like a novel for me. For example, Pushkin. I have a fantastic biography of Pushkin and this is how I started to love Pushkin, through the biography. And the author, an English guy, was lucky because he got into Russia before they closed the archives and had acces to all the details, about his connection to the revolutionaries, about his fatal duel. Fantastic! Today you couldn’t write the same biography. Putin closed every archive.

Also, because Kafka is very important to me and his novels are put together, in fact, from short proses – not like Thomas Mann or Proust, whose prose is flowing –, I like that form also, this kind of Hasidic tale telling, which is always giving an example, an anecdote, an allegory. Kafka is very concise and was greatly influenced by Hasidic literature.

(What about theater? I ask – n.r.) I worked a lot in the theater, for thirty years, and I wrote many plays. I read plays for work and also when I translate. It’s not so easy to read plays, you have to learn how to do it. Because what is it? Names, sentences. Names, sentences. How do you create a world of it? That, you have to learn. You have to direct it in your head, in fact.

Are there genres you avoid? Like science-fiction, perhaps.

Science-fiction, yes. It doesn’t fascinate me. And horror. Nothing. But I enjoy crime novels – the good ones. For example, I like very much this English woman writer… (He thinks, so I suggest Agatha Christie – n.r.) No, not her, another one, a brutal one. Agatha Christie was the favorite author of my poet friend, Petri György. Hitchcock made films of her novels, she’s good, she’s very brutal. My head is filled with Proust right now and I can’t remember a lot of things, he’s a world in itself. (Patricia Highsmith? – n.r.) Yes, Patricia Highsmith. So we put it together. I like her books very much. I don’t like her, she’s a very hard person, but her books, yeah. (I tell him I’ve never met somebody with such strong opinions about both the books and their authors – n.r.) Maybe I’m even more interested in people’s lives.

One of my favorite books is Plutarch, Parallel Lives. And I read it when I was in middle school. You know Parallel Lives? (I admit to ignorance – n.r.) You should read it in the next thirty years. It’s the most fantastic collection of human stories – 30 or 40 lives are in that book, or more. He puts Greek and Roman biographies in parallel – so Julius Caesar has Alexander the Great, Cicero has a Greek counterpart, Demosthenes. That is why it’s called Parallel Lives. He collected all the known facts, Plutarch, about these people and you come to realize that what is fascinating in life is that it is totally accidental and absolutely necessary. And it’s two things happening at the same time. The Greeks and the Romans had this fantastic relationship with fate, much more than we have today. Many Shakespeare plays are coming from that book. When you have a little time, this is something you have to read. (I say I will and that I will also try to read Ulysses at some point – n.r.)

If you start Ulysses, get a good compendium and don’t be ashamed about it, because you need it. You know, when he first published the book and it was instantly famous because of certain parts – obscenity or whatever, the scandal –, he realized that the critics understand only a fragment of it, so he started to tell them what is the system of the book. Every chapter has a symbol and every character has a color, it’s an organ of the body. And he had to tell it, because he realized nobody would get it. And they did start to put it together and it helped people to understand Ulysses. If you want to go up to Kilimanjaro, you have to train, you have to learn the dangers, you have to be fit, and the same thing happens with Joyce. And Proust, also. And this is something most people don’t want to do. Come, book, and be good to me. I will tell you if you’re good or not. But there are certain authors where you have to do the work. No way out of it.

I am very lucky because in 2010 I was asked to teach at the University of Theater and Film Arts in Budapest and at first I refused, claiming I don’t have time, I don’t want to fall apart etc. I said to the guy – we’ve just met yesterday, he is Tamás Ascher a brilliant director, and we spoke about this: “You know, my problem is that I fall apart all the time and I don’t want to fall apart again.” And he replied: “This will put you together.” And he was right! Because I started to teach Joyce, I started to teach Shakespeare’s sonnets, I started to teach Don Quixote and I had to prepare well. I had to put it together to be able to speak about them. And that gave me another level of understanding.

Recommend a couple of less known books that you absolutely loved.

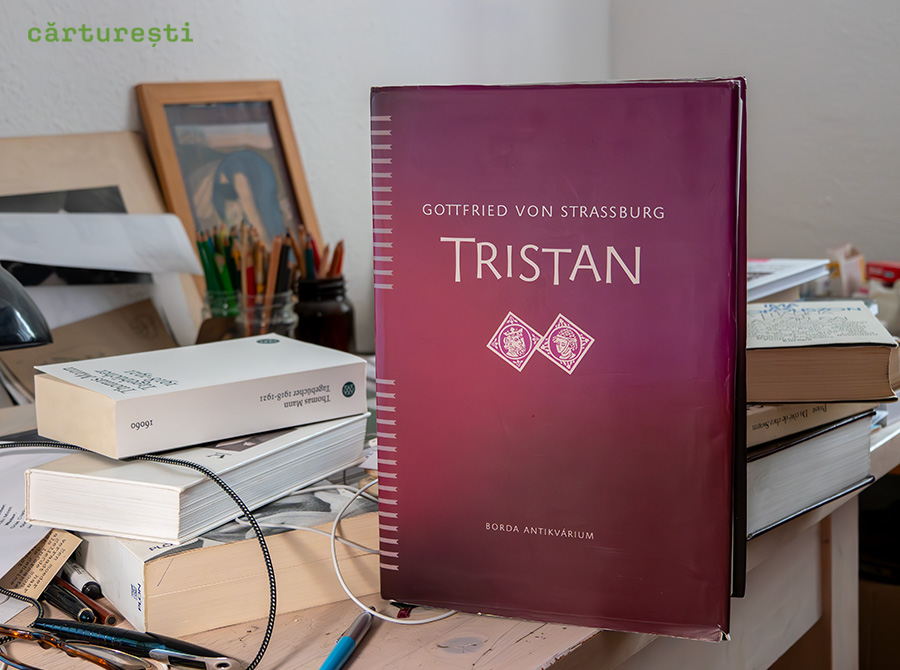

That would be Das Echolot by Walter Kempowski. Oh, and I wanted to show you this book, which became very important to me. It’s the Hungarian translation of Gottfried von Strassburg’s verse novel Tristan, written in the old German – and my friend László Márton translated it. Maybe you should also visit him, because he has a wonderful library. This is a book that you cannot buy in the bookshop. A private person – a passionate guy, a millionaire – ordered it from my friend, and then he published it in only two hundred copies, and you can’t get it anywhere! Look at the beauty of it! I don’t know if you ever saw a Wagner opera or know the Tristan story. It is a basic love story, like Romeo and Juliette, which influenced Proust, Péter Nádas and many more. And it’s only through this book that I understood the whole thing, because it’s the original version.

This is another important book for me, which I found accidentally. Nan Goldin, have you heard her name? She’s an American photographer. I found it in a bookshop in Rome and I had to buy it, because I collect art books as well. It’s a very expensive book, but it was half price – 50 dollars or so – and I could afford it. This is The Garden of the Devil. Nan Goldin. Very brutal book, with motherhood, love making also, with pregnancy and pictures of herself. She photographed herself after she was beaten up by her boyfriend. She lived in certain communities and they allowed her to photograph them. I’ve never heard of her before. So I found this book and it came out she’s one of the greatest photographers.

Tell me the story of an object on your library shelves.

Let’s go into the other room. (We go back to the study, where our discussion started – n.r.) Here is an object: a pig, you can open it and put stuff inside. It was the totem animal of my friend, the poet Petri György. He gave it to me before he died. And this one. (He shows me a small bottle with a faded label – n.r.) My mother did beautiful embroideries and these are her needles – by the way, this is my grandmother’s broidery (He shows me a photo on his desk – n.r.)

Everything is packed away, so I can’t show you the real stuff. So my mother put the needles inside and what is written here is Ebéd. Lunch. Here she kept the pills that my father had to take during meals – my father was a very ill person, maybe you remember from the book. She was a very tragic figure for me, my mother. All these needles and… Lunch. She ate needles all her life. She died almost forty years ago and she is and she will remain a very important part of myself and also of my books.

Ema Cojocaru is a photographer, reader, and literary blogger. She writes book reviews on Lecturile Emei and has published short stories in Revista de povestiri. Every month, she moderates the book club Bibliobibuli.

Any book lover has curiosities about other people’s libraries. That’s how the idea for the column “A Writer’s Library” came about, where contemporary authors are interviewed and photographed alongside their book collections.

There are no comments

Add yours